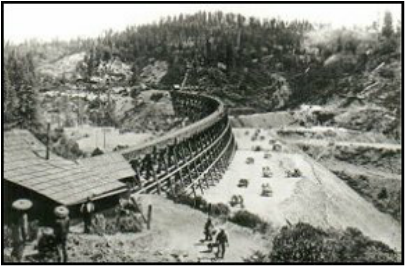

During the gold rush it had been estimated that 48,070 Chinese came to California to work in the mines. As the diggings begun to decline, over 10,000 Chinese laborers were recruited by the Central Pacific Railroad for bringing the railroad over the Sierra.

Reports tell of Chinese workers being lowered in baskets down two thousand foot cliffs to set explosives. Many lost their lives in the blasting of the granite. Following the completion of the railroad through the Truckee basin in 1869, approximately 1,000 Chinese workers and their families decided to make Truckee their home.

The experience of the Chinese in Truckee is merely a microcosm of the attitudes that generally prevailed in the state. Violent prejudice developed in the mid-1870s as a post Civil War depression hit the nation. Up and down the Pacific Coast, the Chinese became the scapegoats and were blamed for depriving white laborers of their jobs.

On Sunday morning, June 18, 1876, shortly after midnight, seven armed white men silently set out from C.W. Humphrey’s Saloon and followed the old trail north along Trout Creek which led to two small cabins about one and a half miles northwest of Truckee, near today’s Tahoe Donner subdivision.

Sleeping inside the cabins was a crew of six Chinese woodcutters who had been hired by Joseph Gray to cut wood and gather firewood. Earlier that week, the workers had been warned by the same men to stop their work and leave town. The warnings may not have been understood and were not heeded.

At approximately one o’clock a.m., the gunmen surrounded one of the cabins. Two men poured coal tar onto the roof and lit it on fire, then took cover and waited. Within a minute or two, several terrified workers ran out of the cabins and began throwing water on the fire.

Without warning, the perpetrators opened up on them with their weapons. One Chinese worker, Ah Ling, was immediately shot, receiving a full charge in the left side of his abdomen. Several others were wounded before realizing they were being fired upon. The terrified woodcutters fled into the woods and hid until daybreak. Eleven shots were fired and the cabin was burned to ashes.

The same group then raided another camp, again, terrorizing another group of Chinese workers. Fortunately, nobody was killed or wounded in the second raid.

Early the next morning, the weary survivors carried the body of their mortally wounded companion to town, passing families on their way to church. They were met by constables Hank Greeley and Jake Cross at Gray’s cabin. Joseph Gray immediately summoned Dr. Curless but by the next morning Ah Ling was dead.

Only one of the woodcutters, Ah Fook, spoke English. He informed the lawmen of what had transpired but was unable to identify the culprits. Constable Cross promptly headed for the depot and had a telegraph sent to Nevada City. The following day an investigation began which culminated in Truckee’s most widely publicized criminal trial.

Six years earlier, hostilities had began to grow as Truckee’s Chinese population swelled to approximately 1,400. The town had the largest Chinatown in the Sierras, encompassing the entire hillside below Rocking Stone Tower. Many townspeople believed that crowded wooden shanties posed a serious threat of fire to the rest of the community.

These concerns were inflamed by frequent editorials published by the Truckee Republican telling of Chinese opium houses, prostitution and petty crimes committed both in Chinatown and along Jibboom Street. At the same time, Sisson, Wallace & Co. was publishing full-page advertisements offering inexpensive Chinese labor to be furnished on short notice, infuriating competing white workers.

In 1872 a riot exploded in Chinatown over the ancient practice of buying and keeping women as slaves. A gunfight with deputies resulted in a terrible fire and the death of two men. Another terrible riot in 1874 fueled anti-Chinese sentiments. Continuing reports of stabbings, murders and other illegal activities among the Chinese population led to the formation of several vigilante committees and the construction of a fire-proof jail, strategically located near Chinatown on Jibboom Street.

In May 1875, a fire of suspicious origin consumed most of Chinatown. After each fire, Truckee’s beleaguered and maligned Chinese rebuilt their rickety shacks on the same site. By this time, many of the towns leading citizens began meeting regularly to find ways to drive the Chinese out of town.

In 1876, a white supremacist group, known as the Order of Caucasians or the "Caucasian League," was established. The secret society had more than 300 members in Truckee and 10,000 members throughout California. Its membership included many of the town’s most prominent citizens, such as grocer Hamlet Davis, and physician, Dr. William Curless.

Meetings were openly held in the town every Saturday evening. New members were inducted with secret initiations. The primary goal of this group was to extinguish, through any means, the Chinese population from Truckee and from California.

The plan to raid the cabins at Trout Creek was the result of a drunken and angry meeting that took place in the smoke filled meeting hall above the Capitol Saloon on June 18, 1876. Many people in town were surprised when the murder of Ah Ling made the headlines of newspapers throughout the state. It became known as "The Trout Creek Outrage." The Virginia City Territorial Enterprise referred to it as "one of the most cold blooded and unprovoked murders ever recorded." The Stockton Herald published unfavorable assertions about the people of Truckee, calling it "The Truckee War."

Prompted by the enormous amount unfavorable publicity, Truckee Republican (predecessor to the Sierra Sun) felt compelled to respond on June 21, 1876 by declaring, "The citizens of Truckee are greatly incensed over this outrageous, fiendish, cowardly act." Yet, many townspeople were not enraged and although they may have known who committed the crime, they remained silent.

Detectives from Nevada City dispatched to Truckee to ferret out the perpetrators worked unsuccessfully for weeks. Eventually, a few sympathetic businessmen in town raised a reward of $1,000. Governor Irwin offered $300 and the Chinese raised $200 among themselves.

Constable Cross, who led the investigation, received an anonymous threat that he would be killed if he persisted, but this made him more determined then ever to solve the crime. The Central Pacific Railroad sent its best detective, Len Harris, to assist Cross in the investigation.

The hard work of the lawmen paid off. Confessions of Calvin McCullough and G.W. Getchell led to indictments for arson and murder against their fellow conspirators, Fred Wilbert, Frank Wilson, G.W. Mershon, William O’Neal and James Reed. A search of Domingo Reed’s brothel on Jibboom Street resulted in the discovery of Reed’s double-barreled shotgun that had been recently fired.

The morning of September 5, 1876 began a long and highly publicized trial in Nevada City. Although all seven men were indicted, only O’Neal was brought to trial for murder. The others, who were well known adequately represented, faced lesser charges of arson.

O’Neal was an employee of the Central Pacific railroad and had only arrived in Truckee a short time before the incident. James Reed was best known and well liked and although there was much reason to believe that he fired the fatal shots at Ah Ling, he was able to evade indictment for murder.

Tall and handsome and always impeccably dressed, Reed was widely known for his proficiency with firearms. A month earlier he had "accidentally" fired his shotgun into Chinatown, wounding a Chinese man in the leg. He was a tough man and enormously popular in the saloons on Commercial Row. Reed knew nearly every man in town as well as all the ladies on Jibboom Street. Many feared him but most respected him.

The best lawyers in Truckee appeared before the grand jury to defend the parties. Among them was Truckee’s most respected attorney, Charles F. McGlashan. A festive atmosphere prevailed as hundreds of people from Truckee and reporters from newspapers throughout California crowded into Nevada City’s hotels. Many had to camp out on the courthouse lawn. Witnesses for the defense included John Moody, proprietor of the Truckee Hotel, and Caucasian League president, Hamlet Davis.

On September 27, 1876, opening statements were made. During the trial, Getchell and McCullough, who had turned state’s evidence, were placed on the stand and told their stories, corroborating each other in every detail. They testified that the plot was initiated by the Caucasian League with the intention that after the cabins were set on fire the Chinese workers would be shot as they came out.

Calvin McCullough described how Reed loaded his shotgun with wire shot then headed out with the others above Elle Ellen’s mill on Trout Creek. Upon arriving at the cabin he told how Getchell threw coal oil on the roof and set it on fire. He recalled that he and the other gunmen waited in the darkness until Ah Ling came out to with a bucket and how all the guns went off just as he was throwing water in the fire.

McCullough testified that the gunmen then went to another cabin a short distance away where Getchell again poured coal oil on it and set it on fire. As the terrified men began to come out, they were fired on but they immediately ran into the woods and none were killed.

Upon intense cross-examination, McCullough was discredited when it was disclosed that he had served 60 days in jail in Nevada for stealing a pair of boots and was jailed in Austin Nevada for stealing horses. He further admitted to being in jail in Virginia City and even to having served a year in San Quentin. The defense scored significantly when McCullough testified that when he confessed his role in the crime, Constable Cross offered him $500 of the reward when the conviction was made. This fact that was later supported by the testimony of Fred Wilbert.

G.W. Getchell admitted that he attended the meeting of the Caucasian League that adjourned at 10 p.m. Eleven men remained who devised a plan to give the Chinese a "scare" by setting their cabins on fire and shooting off their guns. The plans progressed as they later shared several bottles of whiskey at C.W. Humphrey’s saloon. He confirmed that James Reed carried his own double-barreled shotgun.

Mershon testified that he knew where the two camps were and suggested "giving the Chinese a scare." He recalled that the weapon used in the raid was obtained from Frank Wilson and James Reed who refused to loan his guns unless he went with them. He described how the men armed themselves at Wilson’s home and that Reed loaded his shotgun with deadly wire shot while the others strapped on side arms. They then set out for Trout Creek where Getchell poured coal oil on the cabin and set fire to it.

Ah Fook, a companion of Ah Ling, testified to being awakened by the flames that he and his companions tried to extinguish with three cans of water. When they were unable to do so, Ah Ling took a can and ran outside toward the creek that was only a few feet away and was immediately gunned down. With bullets whizzing over his head, he told how he dragged Ah Ling back into the blazing cabin while the others tried to shield themselves from the flames with blankets.

Finally forced to evacuate their home by the searing heat, they carried their wounded companion across the creek, covered him with a blanket; and then hid in the bushes until dawn. Ah Fook recalled that there were six or seven armed men, all dressed in black who fired on them from a distance of about 25 feet from the cabin. He stated that they remained hidden until daylight, and then quietly carried their companion into town where they procured the services of Dr. Curless.

Dr. William Curless, himself a member of the Caucasian League, recalled tending to the victim, dressing his wounds and then leaving him. In desperation, a Chinese doctor was summoned who came and placed a poultice of pounded leaves on the wound, but by the next day Ah Ling was dead. "I knew he was mortally wounded when I dressed the wounds," Curless stated. "It was quite a large bullet hole."

The defense placed some fifty witnesses on the stand by whom the testimony of the two prosecuting witnesses was overwhelmingly contradicted and an alibi was provided for each of the implicated men. In all, over 75 witnesses were examined.

Given the blanket of protective testimony thrown about the accused parties, the prosecution eventually abandoned the case in despair. After deliberating nine minutes, the all male jury returned a verdict of not guilty as to O’Neal, while a nolle prosequi was entered as to the arson charges in the other six cases. All the defendants were released on their own recognizance.

News of the acquittals was unfavorably received. On October 3, 1876, The Sacramento Daily Union stated, "The general conclusion to be reached, therefore, is that certain white men did perpetrate this outrage and though those accused have been acquitted, the people of Truckee cannot clear themselves of the responsibility so easily."

The Reno Evening Gazette declared on October 5, 1876, "We are forced to think that the whole transaction was a maliciously arranged plot and are inclined to believe further, that when the whole history of this transaction is written, it will reveal a phase of human depravity and cupidity that would cast a gloom over the dark shades of hell."

On October 3, 1876, the Nevada City Daily Transcript reported that a number of people in Truckee "brought out a big cannon and fired a salute." It was further reported "that there was considerable excitement in Truckee in regard to constable Jake Cross."

Three dispatches were sent to the District Attorney Gaylord and Sheriff Clark asking them to protect constable Cross. "The cause of the feeling against Cross," said the Nevada Daily Transcript, "is on account of his working up a case and causing the arrest of five men who were afterwards indicted by the Grand Jury for the crime and murder and arson at Trout Creek."

W. F. Edwards, editor of the Truckee Republican, defended the town by denying rumors of a plot to assassinate Jake Cross, "The strongest point entirely overlooked at the trial," he stated, "was that two different Chinamen at different times, had been murdered on this very spot by Chinamen themselves."

While few doubted that the deed was committed as related, most public opinion at the time sanctioned the verdict. Since most of the perpetrators were well known and respected citizens in Truckee, the crime could not be proven in a court of law at the time.

The History of Nevada County, published in 1880, noted that there was no case in the criminal annals of Nevada County that attracted such attention and interest in Truckee and abroad. A Congressional Commission was dispatched to California to inquire into other injustices committed against the Chinese.

During the late 1870s, anti-Chinese sentiments continued as Truckee’s Chinese population swelled to nearly 2,000. On October 28, 1878, Chinatown was burned down again. This time they were forbidden to rebuild. Amid freezing temperatures, the hungry Chinese population was forced to relocate across the river on land donated by the Central Pacific Railroad.

Crowds cheered as the remains of old Chinatown were torn down. Young boys threw rocks as the homeless Chinese carried their few remaining possessions through town while adults idly stood by. Whites who dared to assist the Chinese were themselves threatened.

Newspapers in San Francisco used the term "total anarchy" in describing the cruel heartless ways that Truckee treated its Chinese citizens who had only a few grains of rice left to feed themselves. Things might have been worse had not a few Chinese managed to obtain a supply of rifles and ammunition to protect their families.

The Chinese economic strength was finally destroyed in Truckee in a general boycott during 1885-1886 when the "Safety Committee of Truckee" was formed. The boycotting committee, under the leadership Charles Fayette McGlashan, published a manifesto wherein every businessman in Truckee pledged himself "never in the future to buy from, sell to, or barter with Chinamen for anything of value." Within five weeks, Truckee’s entire Chinese population had left town. The town held a torchlight parade in celebration of the event.

As a footnote, James Reed was elected Truckee’s Constable, replacing Cross. Although he was an effective lawman he remained sympathetic to vigilante groups until 1891, when his career culminated in a violent gunfight with another constable, Jacob Teeter, in which Teeter was killed. The circumstances of the shooting remain a subject of controversy among local historians to this day but many believe that their feud began following the events of 1876.

The Chinese made a monumental contribution in their role in the completion of the Central Pacific Railroad in 1869. Truckee became a leader in the expulsion of the very people who helped make the town possible, with boycotts and exclusion laws. Perhaps their treacherous passage over the Summit into a new land became an omen for the life fraught with antagonism and alienation which later confronted them.

The actions of Truckee’s early townspeople cannot be remembered with pride. What had begun as a viable concern evolved into an atmosphere of pervasive racism. It happened without decorum, without reason. Such torment and hatred must be known and understood as a part of a time and a place in history, so that it is never repeated.

Reports tell of Chinese workers being lowered in baskets down two thousand foot cliffs to set explosives. Many lost their lives in the blasting of the granite. Following the completion of the railroad through the Truckee basin in 1869, approximately 1,000 Chinese workers and their families decided to make Truckee their home.

The experience of the Chinese in Truckee is merely a microcosm of the attitudes that generally prevailed in the state. Violent prejudice developed in the mid-1870s as a post Civil War depression hit the nation. Up and down the Pacific Coast, the Chinese became the scapegoats and were blamed for depriving white laborers of their jobs.

On Sunday morning, June 18, 1876, shortly after midnight, seven armed white men silently set out from C.W. Humphrey’s Saloon and followed the old trail north along Trout Creek which led to two small cabins about one and a half miles northwest of Truckee, near today’s Tahoe Donner subdivision.

Sleeping inside the cabins was a crew of six Chinese woodcutters who had been hired by Joseph Gray to cut wood and gather firewood. Earlier that week, the workers had been warned by the same men to stop their work and leave town. The warnings may not have been understood and were not heeded.

At approximately one o’clock a.m., the gunmen surrounded one of the cabins. Two men poured coal tar onto the roof and lit it on fire, then took cover and waited. Within a minute or two, several terrified workers ran out of the cabins and began throwing water on the fire.

Without warning, the perpetrators opened up on them with their weapons. One Chinese worker, Ah Ling, was immediately shot, receiving a full charge in the left side of his abdomen. Several others were wounded before realizing they were being fired upon. The terrified woodcutters fled into the woods and hid until daybreak. Eleven shots were fired and the cabin was burned to ashes.

The same group then raided another camp, again, terrorizing another group of Chinese workers. Fortunately, nobody was killed or wounded in the second raid.

Early the next morning, the weary survivors carried the body of their mortally wounded companion to town, passing families on their way to church. They were met by constables Hank Greeley and Jake Cross at Gray’s cabin. Joseph Gray immediately summoned Dr. Curless but by the next morning Ah Ling was dead.

Only one of the woodcutters, Ah Fook, spoke English. He informed the lawmen of what had transpired but was unable to identify the culprits. Constable Cross promptly headed for the depot and had a telegraph sent to Nevada City. The following day an investigation began which culminated in Truckee’s most widely publicized criminal trial.

Six years earlier, hostilities had began to grow as Truckee’s Chinese population swelled to approximately 1,400. The town had the largest Chinatown in the Sierras, encompassing the entire hillside below Rocking Stone Tower. Many townspeople believed that crowded wooden shanties posed a serious threat of fire to the rest of the community.

These concerns were inflamed by frequent editorials published by the Truckee Republican telling of Chinese opium houses, prostitution and petty crimes committed both in Chinatown and along Jibboom Street. At the same time, Sisson, Wallace & Co. was publishing full-page advertisements offering inexpensive Chinese labor to be furnished on short notice, infuriating competing white workers.

In 1872 a riot exploded in Chinatown over the ancient practice of buying and keeping women as slaves. A gunfight with deputies resulted in a terrible fire and the death of two men. Another terrible riot in 1874 fueled anti-Chinese sentiments. Continuing reports of stabbings, murders and other illegal activities among the Chinese population led to the formation of several vigilante committees and the construction of a fire-proof jail, strategically located near Chinatown on Jibboom Street.

In May 1875, a fire of suspicious origin consumed most of Chinatown. After each fire, Truckee’s beleaguered and maligned Chinese rebuilt their rickety shacks on the same site. By this time, many of the towns leading citizens began meeting regularly to find ways to drive the Chinese out of town.

In 1876, a white supremacist group, known as the Order of Caucasians or the "Caucasian League," was established. The secret society had more than 300 members in Truckee and 10,000 members throughout California. Its membership included many of the town’s most prominent citizens, such as grocer Hamlet Davis, and physician, Dr. William Curless.

Meetings were openly held in the town every Saturday evening. New members were inducted with secret initiations. The primary goal of this group was to extinguish, through any means, the Chinese population from Truckee and from California.

The plan to raid the cabins at Trout Creek was the result of a drunken and angry meeting that took place in the smoke filled meeting hall above the Capitol Saloon on June 18, 1876. Many people in town were surprised when the murder of Ah Ling made the headlines of newspapers throughout the state. It became known as "The Trout Creek Outrage." The Virginia City Territorial Enterprise referred to it as "one of the most cold blooded and unprovoked murders ever recorded." The Stockton Herald published unfavorable assertions about the people of Truckee, calling it "The Truckee War."

Prompted by the enormous amount unfavorable publicity, Truckee Republican (predecessor to the Sierra Sun) felt compelled to respond on June 21, 1876 by declaring, "The citizens of Truckee are greatly incensed over this outrageous, fiendish, cowardly act." Yet, many townspeople were not enraged and although they may have known who committed the crime, they remained silent.

Detectives from Nevada City dispatched to Truckee to ferret out the perpetrators worked unsuccessfully for weeks. Eventually, a few sympathetic businessmen in town raised a reward of $1,000. Governor Irwin offered $300 and the Chinese raised $200 among themselves.

Constable Cross, who led the investigation, received an anonymous threat that he would be killed if he persisted, but this made him more determined then ever to solve the crime. The Central Pacific Railroad sent its best detective, Len Harris, to assist Cross in the investigation.

The hard work of the lawmen paid off. Confessions of Calvin McCullough and G.W. Getchell led to indictments for arson and murder against their fellow conspirators, Fred Wilbert, Frank Wilson, G.W. Mershon, William O’Neal and James Reed. A search of Domingo Reed’s brothel on Jibboom Street resulted in the discovery of Reed’s double-barreled shotgun that had been recently fired.

The morning of September 5, 1876 began a long and highly publicized trial in Nevada City. Although all seven men were indicted, only O’Neal was brought to trial for murder. The others, who were well known adequately represented, faced lesser charges of arson.

O’Neal was an employee of the Central Pacific railroad and had only arrived in Truckee a short time before the incident. James Reed was best known and well liked and although there was much reason to believe that he fired the fatal shots at Ah Ling, he was able to evade indictment for murder.

Tall and handsome and always impeccably dressed, Reed was widely known for his proficiency with firearms. A month earlier he had "accidentally" fired his shotgun into Chinatown, wounding a Chinese man in the leg. He was a tough man and enormously popular in the saloons on Commercial Row. Reed knew nearly every man in town as well as all the ladies on Jibboom Street. Many feared him but most respected him.

The best lawyers in Truckee appeared before the grand jury to defend the parties. Among them was Truckee’s most respected attorney, Charles F. McGlashan. A festive atmosphere prevailed as hundreds of people from Truckee and reporters from newspapers throughout California crowded into Nevada City’s hotels. Many had to camp out on the courthouse lawn. Witnesses for the defense included John Moody, proprietor of the Truckee Hotel, and Caucasian League president, Hamlet Davis.

On September 27, 1876, opening statements were made. During the trial, Getchell and McCullough, who had turned state’s evidence, were placed on the stand and told their stories, corroborating each other in every detail. They testified that the plot was initiated by the Caucasian League with the intention that after the cabins were set on fire the Chinese workers would be shot as they came out.

Calvin McCullough described how Reed loaded his shotgun with wire shot then headed out with the others above Elle Ellen’s mill on Trout Creek. Upon arriving at the cabin he told how Getchell threw coal oil on the roof and set it on fire. He recalled that he and the other gunmen waited in the darkness until Ah Ling came out to with a bucket and how all the guns went off just as he was throwing water in the fire.

McCullough testified that the gunmen then went to another cabin a short distance away where Getchell again poured coal oil on it and set it on fire. As the terrified men began to come out, they were fired on but they immediately ran into the woods and none were killed.

Upon intense cross-examination, McCullough was discredited when it was disclosed that he had served 60 days in jail in Nevada for stealing a pair of boots and was jailed in Austin Nevada for stealing horses. He further admitted to being in jail in Virginia City and even to having served a year in San Quentin. The defense scored significantly when McCullough testified that when he confessed his role in the crime, Constable Cross offered him $500 of the reward when the conviction was made. This fact that was later supported by the testimony of Fred Wilbert.

G.W. Getchell admitted that he attended the meeting of the Caucasian League that adjourned at 10 p.m. Eleven men remained who devised a plan to give the Chinese a "scare" by setting their cabins on fire and shooting off their guns. The plans progressed as they later shared several bottles of whiskey at C.W. Humphrey’s saloon. He confirmed that James Reed carried his own double-barreled shotgun.

Mershon testified that he knew where the two camps were and suggested "giving the Chinese a scare." He recalled that the weapon used in the raid was obtained from Frank Wilson and James Reed who refused to loan his guns unless he went with them. He described how the men armed themselves at Wilson’s home and that Reed loaded his shotgun with deadly wire shot while the others strapped on side arms. They then set out for Trout Creek where Getchell poured coal oil on the cabin and set fire to it.

Ah Fook, a companion of Ah Ling, testified to being awakened by the flames that he and his companions tried to extinguish with three cans of water. When they were unable to do so, Ah Ling took a can and ran outside toward the creek that was only a few feet away and was immediately gunned down. With bullets whizzing over his head, he told how he dragged Ah Ling back into the blazing cabin while the others tried to shield themselves from the flames with blankets.

Finally forced to evacuate their home by the searing heat, they carried their wounded companion across the creek, covered him with a blanket; and then hid in the bushes until dawn. Ah Fook recalled that there were six or seven armed men, all dressed in black who fired on them from a distance of about 25 feet from the cabin. He stated that they remained hidden until daylight, and then quietly carried their companion into town where they procured the services of Dr. Curless.

Dr. William Curless, himself a member of the Caucasian League, recalled tending to the victim, dressing his wounds and then leaving him. In desperation, a Chinese doctor was summoned who came and placed a poultice of pounded leaves on the wound, but by the next day Ah Ling was dead. "I knew he was mortally wounded when I dressed the wounds," Curless stated. "It was quite a large bullet hole."

The defense placed some fifty witnesses on the stand by whom the testimony of the two prosecuting witnesses was overwhelmingly contradicted and an alibi was provided for each of the implicated men. In all, over 75 witnesses were examined.

Given the blanket of protective testimony thrown about the accused parties, the prosecution eventually abandoned the case in despair. After deliberating nine minutes, the all male jury returned a verdict of not guilty as to O’Neal, while a nolle prosequi was entered as to the arson charges in the other six cases. All the defendants were released on their own recognizance.

News of the acquittals was unfavorably received. On October 3, 1876, The Sacramento Daily Union stated, "The general conclusion to be reached, therefore, is that certain white men did perpetrate this outrage and though those accused have been acquitted, the people of Truckee cannot clear themselves of the responsibility so easily."

The Reno Evening Gazette declared on October 5, 1876, "We are forced to think that the whole transaction was a maliciously arranged plot and are inclined to believe further, that when the whole history of this transaction is written, it will reveal a phase of human depravity and cupidity that would cast a gloom over the dark shades of hell."

On October 3, 1876, the Nevada City Daily Transcript reported that a number of people in Truckee "brought out a big cannon and fired a salute." It was further reported "that there was considerable excitement in Truckee in regard to constable Jake Cross."

Three dispatches were sent to the District Attorney Gaylord and Sheriff Clark asking them to protect constable Cross. "The cause of the feeling against Cross," said the Nevada Daily Transcript, "is on account of his working up a case and causing the arrest of five men who were afterwards indicted by the Grand Jury for the crime and murder and arson at Trout Creek."

W. F. Edwards, editor of the Truckee Republican, defended the town by denying rumors of a plot to assassinate Jake Cross, "The strongest point entirely overlooked at the trial," he stated, "was that two different Chinamen at different times, had been murdered on this very spot by Chinamen themselves."

While few doubted that the deed was committed as related, most public opinion at the time sanctioned the verdict. Since most of the perpetrators were well known and respected citizens in Truckee, the crime could not be proven in a court of law at the time.

The History of Nevada County, published in 1880, noted that there was no case in the criminal annals of Nevada County that attracted such attention and interest in Truckee and abroad. A Congressional Commission was dispatched to California to inquire into other injustices committed against the Chinese.

During the late 1870s, anti-Chinese sentiments continued as Truckee’s Chinese population swelled to nearly 2,000. On October 28, 1878, Chinatown was burned down again. This time they were forbidden to rebuild. Amid freezing temperatures, the hungry Chinese population was forced to relocate across the river on land donated by the Central Pacific Railroad.

Crowds cheered as the remains of old Chinatown were torn down. Young boys threw rocks as the homeless Chinese carried their few remaining possessions through town while adults idly stood by. Whites who dared to assist the Chinese were themselves threatened.

Newspapers in San Francisco used the term "total anarchy" in describing the cruel heartless ways that Truckee treated its Chinese citizens who had only a few grains of rice left to feed themselves. Things might have been worse had not a few Chinese managed to obtain a supply of rifles and ammunition to protect their families.

The Chinese economic strength was finally destroyed in Truckee in a general boycott during 1885-1886 when the "Safety Committee of Truckee" was formed. The boycotting committee, under the leadership Charles Fayette McGlashan, published a manifesto wherein every businessman in Truckee pledged himself "never in the future to buy from, sell to, or barter with Chinamen for anything of value." Within five weeks, Truckee’s entire Chinese population had left town. The town held a torchlight parade in celebration of the event.

As a footnote, James Reed was elected Truckee’s Constable, replacing Cross. Although he was an effective lawman he remained sympathetic to vigilante groups until 1891, when his career culminated in a violent gunfight with another constable, Jacob Teeter, in which Teeter was killed. The circumstances of the shooting remain a subject of controversy among local historians to this day but many believe that their feud began following the events of 1876.

The Chinese made a monumental contribution in their role in the completion of the Central Pacific Railroad in 1869. Truckee became a leader in the expulsion of the very people who helped make the town possible, with boycotts and exclusion laws. Perhaps their treacherous passage over the Summit into a new land became an omen for the life fraught with antagonism and alienation which later confronted them.

The actions of Truckee’s early townspeople cannot be remembered with pride. What had begun as a viable concern evolved into an atmosphere of pervasive racism. It happened without decorum, without reason. Such torment and hatred must be known and understood as a part of a time and a place in history, so that it is never repeated.