We all know that Stanford is an institution of higher learning near San Francisco. But did you know that the Truckee’s own Stanford is just 6 miles from downtown? That’s right. Towards the end of Coldstream Canyon, you’ll find a tribute to Stanford older than Stanford University.

The first tribute is still visible as a sweeping “horseshoe curve” along the railroad that brings west bound trains from the south side of the canyon to the north side. By the time a west bound train exits Coldstream Canyon, it’s gained 400 feet in elevation. Trains still have to gain 300 in elevation until they disappear into the tunnel under the summit and under part of the Sugar Bowl ski resort.

The Stanford Curve is noteworthy not only because it’s part of the original transcontinental railroad. It’s also only one of 4 locations for railroad horseshoe curves in California, the others being the Cantara loop near Dunsmuir, the Cuesta Grade near San Luis Obispo, and a collection of 5 curves near Fort Bragg on the California Western Railroad. Unlike many horseshoe curves, the view from one side to the other side of the Stanford Curve is obstructed by trees so you have to imagine how grand and magnificent it is.

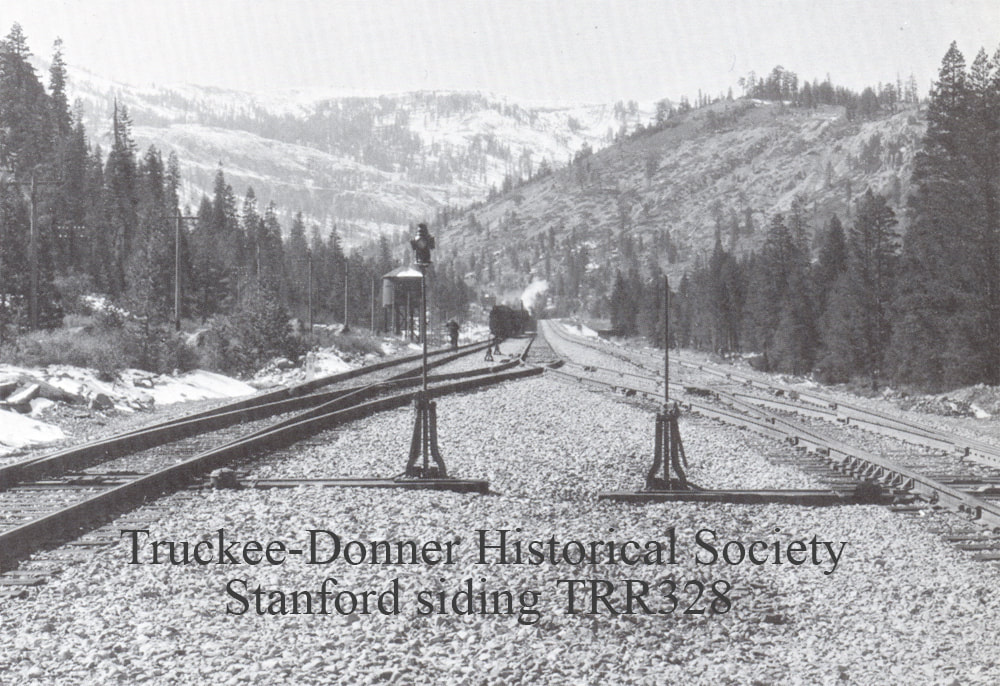

If you visit the canyon, you’ll notice that the shape of the canyon seems perfectly suited for railroad construction techniques of the 1860s. It provides ample distance for gentle elevation gain towards Donner Summit and plenty of space for a wide right-of-way. In fact, there’s so much space, that there was room enough for Stanford Station. Stanford Station may very well be the first building to bear the Stanford name.

Just before a west bound train enters the big curve, there’s a long and flat and straight section of roadbed often sometimes called Stanford Flats. It was in this area that you would have found our Stanford of the Sierra or what was once better known as Stanford Station. One of the records of the area dates back to 1874. In 1879, the area was called Stanford’s Mill. (1). Log flumes carried lumber a mile and half to the station from a mill site even farther up the canyon. (2)

The first tribute is still visible as a sweeping “horseshoe curve” along the railroad that brings west bound trains from the south side of the canyon to the north side. By the time a west bound train exits Coldstream Canyon, it’s gained 400 feet in elevation. Trains still have to gain 300 in elevation until they disappear into the tunnel under the summit and under part of the Sugar Bowl ski resort.

The Stanford Curve is noteworthy not only because it’s part of the original transcontinental railroad. It’s also only one of 4 locations for railroad horseshoe curves in California, the others being the Cantara loop near Dunsmuir, the Cuesta Grade near San Luis Obispo, and a collection of 5 curves near Fort Bragg on the California Western Railroad. Unlike many horseshoe curves, the view from one side to the other side of the Stanford Curve is obstructed by trees so you have to imagine how grand and magnificent it is.

If you visit the canyon, you’ll notice that the shape of the canyon seems perfectly suited for railroad construction techniques of the 1860s. It provides ample distance for gentle elevation gain towards Donner Summit and plenty of space for a wide right-of-way. In fact, there’s so much space, that there was room enough for Stanford Station. Stanford Station may very well be the first building to bear the Stanford name.

Just before a west bound train enters the big curve, there’s a long and flat and straight section of roadbed often sometimes called Stanford Flats. It was in this area that you would have found our Stanford of the Sierra or what was once better known as Stanford Station. One of the records of the area dates back to 1874. In 1879, the area was called Stanford’s Mill. (1). Log flumes carried lumber a mile and half to the station from a mill site even farther up the canyon. (2)

Stanford Station is first mentioned in the Truckee Republican on June 10, 1911 when “Great Excitement” resulted from a false alarm about a landslide. The event was big enough news to be included on the front page. A whopping four sentences summarize the false alarm, the scramble to assemble a work train and the phone call to stop the train from leaving Truckee. The alarm was sent on a “Jerry machine.” I’ve tried to learn what a Jerry machine is, but I have not been successful. (3) From what I can surmise, the phone call was made from another small station between Coldstream Canyon and Truckee called “Champions” about 2 miles east of the Stanford Station.

It always amazes me that these small stations were destinations that people visited frequently. Between Truckee and Norden on the other side of the summit, a traveler would have passed through 10 small stations including Champion, Stanford Station, Andover high above the mouth of the canyon and near the double tunnels, Eder, and Summit stations. There is little evidence today that these stations ever existed, but the Truckee Republican newspaper includes many short stories about the comings and goings of people to and from Stanford Station. The paper reports the activities like a society page more than anything else.

1920 was a notable year with three departures from Stanford Station making the news. In October 1920, “Mr. and Mrs. Martin, who have been spending the summer at Stanford Station, have returned to their home here for the winter.” (4). I suspect the Martins wanted to get out of the area before the snows started.

Another departure from Stanford Station was reported just a few weeks later in 1920 when “Mrs. G. McFarland, who was block operator at Stanford Station, returned to her home in San Francisco last week.”

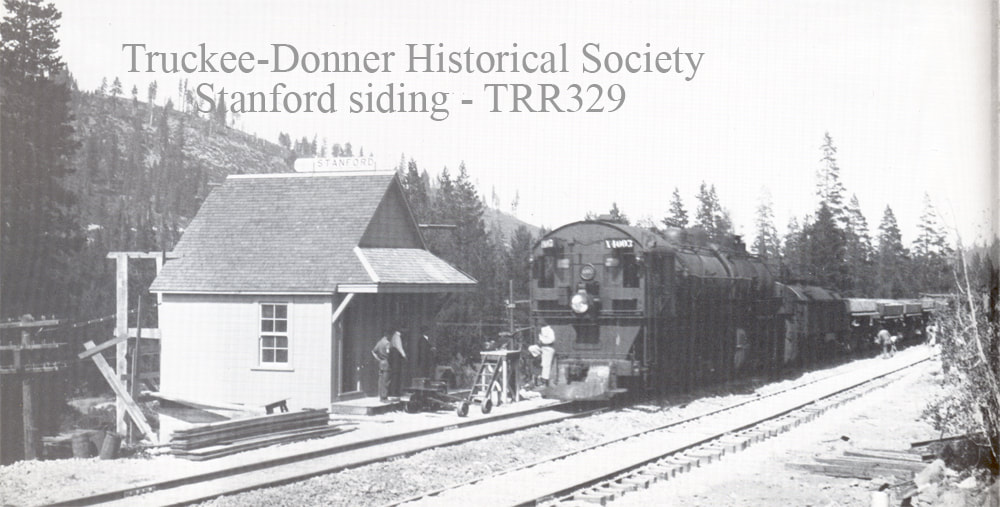

In December of 1920, Mrs. F. Tong and family have moved down from Stanford Station camp for the winter. (5) This is the only reference to Stanford Station as a “camp.” Judging by the photo, the station itself wasn’t very big, so I wonder if there were other buildings in the area. I don’t think Mrs. F. Tong and family would have been camping in tents in December, but you never know. This is the third report of people leaving the station in three months. What was the reason? A corporate shakeup? A departmental reorganization? I have to wonder about the details that aren’t being reported.

In July, 1921, J.O. Palmanter was reported to have left Stanford Station to go to Live Oak signal tower for the duration of the summer. (6)

In January of 1921, “G. Munson, staff operator at Stanford Station,” was “spending his vacation in Sacramento and Carson.” I imagine he was eager to go to warmer and less snowier locations than the back of Coldstream Canyon. And quite a vacation he must have had! It wasn’t until two months later on March 3 that “George Munson, the well-known staff operator at Stanford Station, returned home from his vacation spent at Carson.” This report is notable since it is one of the only reports that somebody returns to Stanford Station. All other reports tell stories about people leaving the station, not returning. (7)

In April of 1922, George Munson is in the news again as the Truckee Republican reports that he visited Sacramento. (8)

It always amazes me that these small stations were destinations that people visited frequently. Between Truckee and Norden on the other side of the summit, a traveler would have passed through 10 small stations including Champion, Stanford Station, Andover high above the mouth of the canyon and near the double tunnels, Eder, and Summit stations. There is little evidence today that these stations ever existed, but the Truckee Republican newspaper includes many short stories about the comings and goings of people to and from Stanford Station. The paper reports the activities like a society page more than anything else.

1920 was a notable year with three departures from Stanford Station making the news. In October 1920, “Mr. and Mrs. Martin, who have been spending the summer at Stanford Station, have returned to their home here for the winter.” (4). I suspect the Martins wanted to get out of the area before the snows started.

Another departure from Stanford Station was reported just a few weeks later in 1920 when “Mrs. G. McFarland, who was block operator at Stanford Station, returned to her home in San Francisco last week.”

In December of 1920, Mrs. F. Tong and family have moved down from Stanford Station camp for the winter. (5) This is the only reference to Stanford Station as a “camp.” Judging by the photo, the station itself wasn’t very big, so I wonder if there were other buildings in the area. I don’t think Mrs. F. Tong and family would have been camping in tents in December, but you never know. This is the third report of people leaving the station in three months. What was the reason? A corporate shakeup? A departmental reorganization? I have to wonder about the details that aren’t being reported.

In July, 1921, J.O. Palmanter was reported to have left Stanford Station to go to Live Oak signal tower for the duration of the summer. (6)

In January of 1921, “G. Munson, staff operator at Stanford Station,” was “spending his vacation in Sacramento and Carson.” I imagine he was eager to go to warmer and less snowier locations than the back of Coldstream Canyon. And quite a vacation he must have had! It wasn’t until two months later on March 3 that “George Munson, the well-known staff operator at Stanford Station, returned home from his vacation spent at Carson.” This report is notable since it is one of the only reports that somebody returns to Stanford Station. All other reports tell stories about people leaving the station, not returning. (7)

In April of 1922, George Munson is in the news again as the Truckee Republican reports that he visited Sacramento. (8)

Is there more to learn about George Munson? Who was he and why was he “well known?” Interestingly enough, Munson and Palmanter (also printed as Polmanteer, Polmanter) are both listed in the Lodge Directory of the October 3, 1918 Truckee Republican. (9) and for many years before and after that.

Munson is in the news again in 1918 in the middle of World War I where we learn that he had travelled to Nevada for a draft examination and that, “After a narrow examination he was exempted by the Board for the reason that they did not deem it advisable to rob the country of a man of his qualifications and good looks.” (10). So now we know he was apparently “well known,” maybe handsome and unable to participate in WW I. As if to provide a snapshot in time about where Truckee was on the path to becoming a modern town, the same article notes that the platform of the Truckee station received new lights providing “daylight illumination.” I can imagine Truckee residents heading to the station at night just to look at the lights. I know I would have.

Munson and Palmanter again appear in the news together in September of 1920 where it’s noted that, “Mr. Polmanteer and family and George Munson, block operators, have been transferred from Champion station to Stanford station.” (11). Just a few months later we see the reports of three different sets of people leaving the station.

I’ve taken a few adventures down Coldstream Canyon myself and have seen the Stanford Curve. There’s a culvert underneath the tracks that usually has water flowing through it, but it also serves as an access point to properties even farther up the canyon. The first time I ventured into the canyon was sometime in the late 70s on a guided horseback trip. We probably ended that day with dinner at Pejo’s that was located at Donner Gate and was famous (at least in my mind) for its curiously named “Donner Burger.” I walked back to the curve once with my brothers and saw no one else in the canyon at that time. I’ve even driven back there a few times. The original Emigrant Trail runs down the canyon near the creek in places, so if you want to experience what the pioneers may have experienced, walk along the dirt road by the creek. In my experience access to the canyon wasn’t always guaranteed as the gate at the mouth of the canyon was never reliably open or unlocked.

If you want to visit our Stanford of the Sierra, be cautious. Trains fly up and down the canyon with amazing speed. However, when the trains are gone, it’s easy to forget that the hustle and bustle in Truckee is just a few miles away. You can easily feel isolated and alone near Stanford Station now, but hopefully you can imagine and wonder the lives, the personalities, and the activity at the Stanford of the Sierra.

Munson is in the news again in 1918 in the middle of World War I where we learn that he had travelled to Nevada for a draft examination and that, “After a narrow examination he was exempted by the Board for the reason that they did not deem it advisable to rob the country of a man of his qualifications and good looks.” (10). So now we know he was apparently “well known,” maybe handsome and unable to participate in WW I. As if to provide a snapshot in time about where Truckee was on the path to becoming a modern town, the same article notes that the platform of the Truckee station received new lights providing “daylight illumination.” I can imagine Truckee residents heading to the station at night just to look at the lights. I know I would have.

Munson and Palmanter again appear in the news together in September of 1920 where it’s noted that, “Mr. Polmanteer and family and George Munson, block operators, have been transferred from Champion station to Stanford station.” (11). Just a few months later we see the reports of three different sets of people leaving the station.

I’ve taken a few adventures down Coldstream Canyon myself and have seen the Stanford Curve. There’s a culvert underneath the tracks that usually has water flowing through it, but it also serves as an access point to properties even farther up the canyon. The first time I ventured into the canyon was sometime in the late 70s on a guided horseback trip. We probably ended that day with dinner at Pejo’s that was located at Donner Gate and was famous (at least in my mind) for its curiously named “Donner Burger.” I walked back to the curve once with my brothers and saw no one else in the canyon at that time. I’ve even driven back there a few times. The original Emigrant Trail runs down the canyon near the creek in places, so if you want to experience what the pioneers may have experienced, walk along the dirt road by the creek. In my experience access to the canyon wasn’t always guaranteed as the gate at the mouth of the canyon was never reliably open or unlocked.

If you want to visit our Stanford of the Sierra, be cautious. Trains fly up and down the canyon with amazing speed. However, when the trains are gone, it’s easy to forget that the hustle and bustle in Truckee is just a few miles away. You can easily feel isolated and alone near Stanford Station now, but hopefully you can imagine and wonder the lives, the personalities, and the activity at the Stanford of the Sierra.

Notes:

1.http://cprr.org/Museum/CP_MP1_SACTO_RENO.pdf

2.(A History of Lumbering in the Truckee Basin from 1856 to 1936 by Constance Darrow Knowles; WPA Official Project No. 9512373, 1942). https://oac.cdlib.org/search?query=forest;group=Items;idT=UCb112296105

3.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19110610.2.11&srpos=1&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22-------1

4. https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19201028.2.2&srpos=11&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22-------1

5.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19201202.2.22&srpos=15&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22+-------1

6.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19210714.2.4&srpos=6&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22-------1

7.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19210120.2.11&srpos=2&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22+munson-------1 https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19210303.2.22&srpos=3&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22+munson-------1

8.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19220406.2.4&srpos=12&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22-------1

9.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19181003.2.20.3&srpos=40&e=-------en--20-SSTR-21--txt-txIN-munson-------1

10.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19181010.2.14&srpos=119&e=-------en--20-SSTR-101--txt-txIN-munson-------1

11.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19200930.2.15&srpos=154&e=-------en--20-SSTR-141--txt-txIN-munson-------1

1.http://cprr.org/Museum/CP_MP1_SACTO_RENO.pdf

2.(A History of Lumbering in the Truckee Basin from 1856 to 1936 by Constance Darrow Knowles; WPA Official Project No. 9512373, 1942). https://oac.cdlib.org/search?query=forest;group=Items;idT=UCb112296105

3.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19110610.2.11&srpos=1&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22-------1

4. https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19201028.2.2&srpos=11&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22-------1

5.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19201202.2.22&srpos=15&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22+-------1

6.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19210714.2.4&srpos=6&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22-------1

7.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19210120.2.11&srpos=2&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22+munson-------1 https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19210303.2.22&srpos=3&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22+munson-------1

8.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19220406.2.4&srpos=12&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-%22stanford+station%22-------1

9.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19181003.2.20.3&srpos=40&e=-------en--20-SSTR-21--txt-txIN-munson-------1

10.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19181010.2.14&srpos=119&e=-------en--20-SSTR-101--txt-txIN-munson-------1

11.https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SSTR19200930.2.15&srpos=154&e=-------en--20-SSTR-141--txt-txIN-munson-------1

TV/HCS posted 9/10/2021; references corrected from plural Sierras to Sierra 12/31/21 HCS

Editor Notes: Reviewing John Signor's 1985 book, Donner Pass Southern Pacific's Sierra Crossing, there are numerous references to the Stanford Station and the Stanford Curve. References can be found on pages 119 (horseshoe curve at Coldstream, between Andover and Truckee, bottom Stanford siding 1924 called the "Stanford Curve"), 167 (Stanford Curve 1943 troop sleepers roll east on Overland Route), 242, and 271. HCS 2/22/2022