Sierra Nevada Wood and Lumber Company

|

|

The partners provided a lot of the lumber and timbers being used to build the Virginia & Gold Hill Water Company flume which took water from above Incline Village and Marlette Lake through the Carson Range by tunnel. From the top of the Washoe Valley, the water went into seven miles of 12" wrought iron pipe, down 1720 feet and back up again in an inverted siphon. Both Hobart & Marlette were investors in the Water Company, and invested in Virginia City mines.Incline Sawmill

The construction boss of this work was John Bear Overton who would later, as superintendent, become the absolute final word in the operation for Hobart & Marlette, while still running the Water Company in Virginia City. In 1876 Hobart & Marlette moved their mill, following the ever moving front of falling trees further up into Little Valley. In addition to lumber, thousands of cords of firewood was cut for use in the Comstock Lode. In 1878 Hobart & Marlette incorporated into the Sierra Nevada Wood & Lumber Company. The Comstock Lode had hundreds of steam engines that were hungry for four foot split pine and fir, using in excess of 100,000 cords a year. Most of the wood was cut from the tops of trees cut for lumber, but young trees of every size were also cut. Most timber operators clear cut every tree in their tracts, but the Tahoe lands were cut with conservation and second growth in mind. |

A Lakeshore Industry

By November of 1879 the SNW&LC had finished construction on a new larger mill at Crystal Bay on the northeast shore of Lake Tahoe. They referred to it as Overton Bay, because it was J.B. Overton who was in charge of building the sawmill and would run all of the operations from now on. Crystal Bay was actually named, not for its clear waters, but for George Crystal, who filed the first timber claims in the area in the early 1860s.

The SNW&LC had bought and leased over ten thousand acres of timberlands along the eastern mountains of Lake Tahoe. The Ponderosa and Jeffrey Pine trees weren't as large as those found further west in the Sierra Nevada, but these tight grained Carson Range pines made strong timbers to hold up the earth in the ever deepening stopes and shafts under Virginia City. Not coincidentally, the burning map at the beginning of "Bonanza" closely matches the Hobart lands.

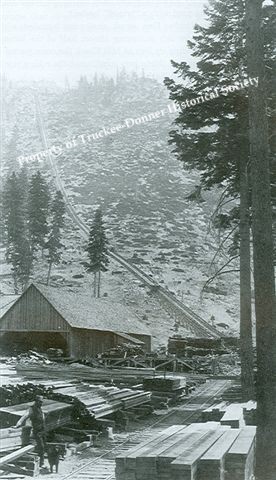

The sawmill's circular saws first cut into logs that were cut in the hills above Crystal Bay, and the lumber was used to build the mill buildings, bunkhouses, cookhouse and other needed facilities on what is now Mill Creek. By the time full operations were underway in early 1881 over 250 loggers, swampers, millmen, woodcutters, camp tenders and mechanics were at work at the mill.

Transportation was a challenge that required some inventiveness. Wagon roads were built from Washoe Valley over the mountain to bring in supplies. A similar road was built up and over the ridge west of Incline Village to Hot Springs, then over the hill to Truckee. Heavy machinery generally was freighted by wagon to either Glenbrook or Tahoe City, then by lake steamer to Overton.

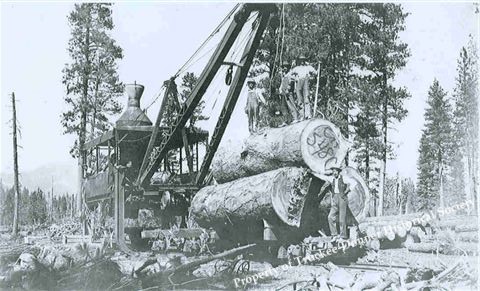

To get the logs from the forest to the mill, oxen skidded the logs through the rough terrain to dry chutes, which were made of two parallel saplings, where horses would speed them to either the mill, the lake, or later, railroad landings. Donkey engines, which are steam powered winches, were also in use to snake logs down the ridges and ravines to landings in the 1890s.

The Incline Railroad

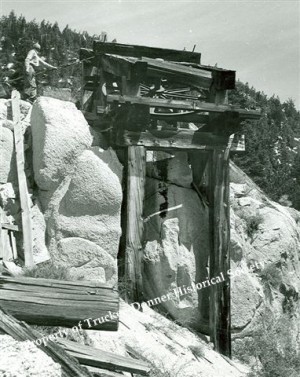

Once the lumber was sawn, it was loaded on to small railcars, and these cars were lifted up the mountain by the famous Incline Railroad. The incline was built in 1880, with the 8000 feet of cable weighing 14,000 pounds, taking almost a week to haul and ship from Truckee. The lift was 1400 feet vertically and the rail line 4000 feet long.

As four loaded cars was being hauled up on the endless cable by the steam engine located at the top, four empty ones was let down the other rail, adding to the efficiency of the operation. The trip took about twenty minutes with one and a half cords of wood or 1500 board feet of lumber being hauled each trip.

Within two months of the incline's opening, the first major accident occurred. Two loaded cars were being hauled uphill, when suddenly, a loud noise startled the mill workers. The cable on the twelve foot bullwheels hummed and shook, and the lumber cars that were nearing the top, stopped their uphill climb.

Slowly at first, then picking up speed quickly, the cars flew downhill. There was nothing to be seen but a streak of fire and smoke streaming out behind the cars. They held the track, thanks to the cable, but that meant they were going all the way to the bottom. There mill hands scrambled to get away, stumbling and tripping in their haste.

The cars hit the bottom of the incline, smashed up the head frame, then launched into the air, and burst into a stand of pine trees with an earth shattering explosion. Metal and wood were splintered into small pieces, with boards piercing the trees to a depth of 8 inches.

The cause of the wreck was attributed to the operator over winding the wrought iron clutch. Apparently Overton's clutch design was less than perfect, as seven cars ran away and were wrecked before a new rachet and cog system was installed preventing any car from dropping further than 4 inches. Even then, accidents happened and men were injured when the cars slipped and were caught by the cogs. The men riding on the cars were often jolted off the cars when the they slammed to a stop.

At the top of the incline, the lumber was dumped into a large wooden V flume that carried it south to the Virginia & Gold Hill water tunnel. There the lumber floated through the mountain in its own flume in the 3994 foot long tunnel, then down into Little Valley, landing down on the Virginia & Truckee Railroad at Lakeview Station, on the divide between Washoe Valley and the Carson City.

By November of 1879 the SNW&LC had finished construction on a new larger mill at Crystal Bay on the northeast shore of Lake Tahoe. They referred to it as Overton Bay, because it was J.B. Overton who was in charge of building the sawmill and would run all of the operations from now on. Crystal Bay was actually named, not for its clear waters, but for George Crystal, who filed the first timber claims in the area in the early 1860s.

The SNW&LC had bought and leased over ten thousand acres of timberlands along the eastern mountains of Lake Tahoe. The Ponderosa and Jeffrey Pine trees weren't as large as those found further west in the Sierra Nevada, but these tight grained Carson Range pines made strong timbers to hold up the earth in the ever deepening stopes and shafts under Virginia City. Not coincidentally, the burning map at the beginning of "Bonanza" closely matches the Hobart lands.

The sawmill's circular saws first cut into logs that were cut in the hills above Crystal Bay, and the lumber was used to build the mill buildings, bunkhouses, cookhouse and other needed facilities on what is now Mill Creek. By the time full operations were underway in early 1881 over 250 loggers, swampers, millmen, woodcutters, camp tenders and mechanics were at work at the mill.

Transportation was a challenge that required some inventiveness. Wagon roads were built from Washoe Valley over the mountain to bring in supplies. A similar road was built up and over the ridge west of Incline Village to Hot Springs, then over the hill to Truckee. Heavy machinery generally was freighted by wagon to either Glenbrook or Tahoe City, then by lake steamer to Overton.

To get the logs from the forest to the mill, oxen skidded the logs through the rough terrain to dry chutes, which were made of two parallel saplings, where horses would speed them to either the mill, the lake, or later, railroad landings. Donkey engines, which are steam powered winches, were also in use to snake logs down the ridges and ravines to landings in the 1890s.

The Incline Railroad

Once the lumber was sawn, it was loaded on to small railcars, and these cars were lifted up the mountain by the famous Incline Railroad. The incline was built in 1880, with the 8000 feet of cable weighing 14,000 pounds, taking almost a week to haul and ship from Truckee. The lift was 1400 feet vertically and the rail line 4000 feet long.

As four loaded cars was being hauled up on the endless cable by the steam engine located at the top, four empty ones was let down the other rail, adding to the efficiency of the operation. The trip took about twenty minutes with one and a half cords of wood or 1500 board feet of lumber being hauled each trip.

Within two months of the incline's opening, the first major accident occurred. Two loaded cars were being hauled uphill, when suddenly, a loud noise startled the mill workers. The cable on the twelve foot bullwheels hummed and shook, and the lumber cars that were nearing the top, stopped their uphill climb.

Slowly at first, then picking up speed quickly, the cars flew downhill. There was nothing to be seen but a streak of fire and smoke streaming out behind the cars. They held the track, thanks to the cable, but that meant they were going all the way to the bottom. There mill hands scrambled to get away, stumbling and tripping in their haste.

The cars hit the bottom of the incline, smashed up the head frame, then launched into the air, and burst into a stand of pine trees with an earth shattering explosion. Metal and wood were splintered into small pieces, with boards piercing the trees to a depth of 8 inches.

The cause of the wreck was attributed to the operator over winding the wrought iron clutch. Apparently Overton's clutch design was less than perfect, as seven cars ran away and were wrecked before a new rachet and cog system was installed preventing any car from dropping further than 4 inches. Even then, accidents happened and men were injured when the cars slipped and were caught by the cogs. The men riding on the cars were often jolted off the cars when the they slammed to a stop.

At the top of the incline, the lumber was dumped into a large wooden V flume that carried it south to the Virginia & Gold Hill water tunnel. There the lumber floated through the mountain in its own flume in the 3994 foot long tunnel, then down into Little Valley, landing down on the Virginia & Truckee Railroad at Lakeview Station, on the divide between Washoe Valley and the Carson City.

|

Hobart’s operation hired experienced loggers from all over the west, including many from Truckee. Charley Barton, a master logger who logged for most everyone in the 1870s, started logging on contract for SNW&LC in 1883, and started a family relationship with the company that would last for decades. |

Loyal Employees

Working as a contractor was veteran Tahoe-Truckee lumberman Gilman Folsom, who had been a partner in a sawmill at Clinton below Boca from 1870 to 1880. In 1880 Folsom partnered with Sam Marlette and they took up a 40,000 cord a year wood cutting contract that employed over 400 men year round, and starting contract logging for the company the following year.

The company also hired Chinese workers, mostly for menial tasks and most of the wood cutting. As Truckee area lumbermen were being boycotted by white laborers for hiring Chinese workers and were responding by firing the Chinese, SNW&L took the opposite approach and hired more Chinese and fired the whites. While the whites were laid off in winter, the Chinese cut firewood in the mountains throughout the fiercest storms the Carson Range could offer.

By 1883 SNW&LC owned 70,000 acres north of Truckee in the Prosser, Sagehen Creek and Little Truckee River. Rumors constantly circulated around Truckee in the 80s and early 90s that Hobart was going to buy an existing sawmill or build a new one and start logging these forests.

While the Carson Range lands were the center of Lake Tahoe operations, Walter Hobart continued to invest in timberlands on the north and west shores of Tahoe. Enough timber had been purchased to last almost to 1900 if all went according to plan. The future looked bright.

Land of Lumber and Fertile Soil

The village of Incline, the sole owner and business being the SNW&LC, had applied for a post office upon moving to lake Tahoe from Little Valley in 1880. It took four years for the Post Office to grant a fourth class office with Gilman Folsom as Postmaster. The village near the mill, containing a store, a boardinghouse, a stable and a few cabins also had daily steamer service in the summer and weekly in the winter. Now it was on the map.

Winter was tough on the men and the company, with most of the work stopping and the mill closing down after the last logs were cut. Woodcutting continued through storms or blue skies. Most of the loggers and millmen spent the winter on ranches in the Nevada valleys. In the winter of 1884 a mile of V flume on a trestle some 80 feet high, was blown down up in Little Valley, but was rebuilt in the snow in only eight days.

By 1884 Gilman Folsom was cutting sawlogs on the southeast shore of Lake Tahoe. These logs and others from around Lake Tahoe were rolled into the lake, cabled together to form rafts and towed by the steamboat Niagra to Sand Harbor. The log landing at Incline was too sandy and unprotected, so Sand Harbor was chosen for the log landing. There the logs were pulled by steam engine onto narrow gauge flatcars that were hauled back to the sawmill by a wood fired locomotive.

Surprisingly the area around Incline, with its mild climate and good soil was a garden spot. SNW&LC had acres of gardens that solved the problem of shipping in fresh food from the Carson and Washoe Valleys. They grew potatoes, onions, lettuce, corn, cabbage, turnips, radishes, and several acres of grain and hay for animal feed.

The Washoe Connection

When the grain field was first cleared, it was early in the spring, and just as they were ready to plant, Captain Joe, Chief of the Washoe, came to Gilman Folsom and told a tale of woe.

Once, all this was land was ours. We killed the deer and bear all over the mountains. When the white man came and took away all our land, except this one little spot, where the creek comes down the mountain. Here we came to camp and hunt rabbits and catch fish. Here we lived every summer and we buried our dead. Now you want to take this one last little resting place from us.

Folsom and part owner Sam Marlette were too tender hearted to resist the pleadings of the eloquent children of the forest and so they abandoned the field, and moved uphill a mile away where they cleared another field for grain. That pleased the Washoe it seemed, at least for that season.

The following year however, Captain Joe was willing to forego his ancestral summer home for a $20 gold piece. Both fields were then planted to feed the hungry lumbermen.

Another of the Truckee area lumbermen who were attracted to the quality operations being run by Hobart & Marlette was James "Nat" Durney. Durney sold his Truckee grocery store in 1884 so he could manage the general merchandise business in Incline.

This deal was worked out because Sisson Crocker Company, who had operations all over the western forests, had contracted to run all of Hobart’s woods crews and Durney was managing that operation as well. After a few years saving his money, Durney moved on to own his own sawmills and stores and was a millionaire by 1910.

Looking for a Blowout

SNW&LC kept a fairly tight rein on alcohol in the company owned town. Still a man needed to blow off steam and the upscale Tahoe resorts didn’t appreciate their hard earned money. A few backwoods dives with watered down tarantula juice could quench that thirst after work, but for a real good time the men rode over to Truckee and kept that town and sometimes its jails quite lively. The biggest Truckee shindig was when the season ended, and all the workingmen descended on the dozens of saloons and the Jibboom Street brothels with the seasons wages in their pockets.

Fire was always a fear in the sawmill, as the combination of dry sawdust and kerosene lamps caused disaster when they came together. So it was no surprise that on June 21, 1886, Captain Overton received a telegram in Virginia City telling him the mill was on fire. As with most sawmills, there was inadequate water supply and mill went up in flames.

Even though timber was becoming depleted, and Virginia City mining had dwindled to a trickle, the sawmill was quickly rebuilt and new machinery installed. Lumber production of

Rails by the Lakeshore

By the mid 1880s lumbermen all over the West were turning to narrow gauge railroads to move sawlogs through the mountains. Hobart & Marlette were no exception. In 1881 they built a two mile spur that ran from the mill to the west towards the California state line. They even designed a new style of logging railcar axles, one that had coupling in the middle, so the log cars could go around sharp corners easier.

In 1888 they started extending the rails south to Sand Harbor, completing it the following year. This allowed them to use that protected bay for unloading log rafts. The log trains rumbled along the lakeshore on a shelf carved out of the rocks above the lake, a route that would eventually become Highway 28.

With Charley Blethen running the original locomotive, a second engine was added in June of 1889 to the Sand Harbor run. The new rail line and additional locomotive was the result of the reduction of timber cutting around Crystal Bay and Folsom’s opening of new logging operations near Zephyr Cove on the southeast corner of the lake. Folsom even named his new town Hobart to keep on the good graces of Walter Hobart.

Throughout the early 90s logging and wood cutting continued full force. The steamer Niagra made frequent trips towing logs from Zephyr Cove to Sand Harbor. And the incline and flume were taxed to full capacity to keep up demand for lumber. The markets had changed with the times, instead of supplying strictly Virginia City, they were shipping lumber throughout the West.

All this despite the death of Walter Hobart Sr. in June of 1892, but his son Walter Jr. took over the management, assisted by a corps of lawyers and advisers. The $800,000 estate included the untouched timberland north of Truckee. It was only a matter of timing to start the relocation.

By the end of 1893 timber was scarce and operations began to wind down. In 1894 they sold the flume to the Carson & Tahoe Lumber Company, the Bliss controlled lumber operation at Glenbrook, that was itself starting to see the end of logging on the horizon. The move was accelerated by a trade of 5,000 acres of timberland that SNW&LC owned between Lake Tahoe & Truckee, to the Truckee Lumber Company who gave an equal amount over north of Truckee, adjacent to the lands that had been bought by Hobart 20 years earlier.

1895 was a year of preparation, as the last of lumber and firewood was shipped, and a crew of surveyors and engineers looked over the land north of Truckee for a new mill site. They soon narrowed down the sites to a flat glacial outwash just north of Prosser Creek, miles north of Truckee.

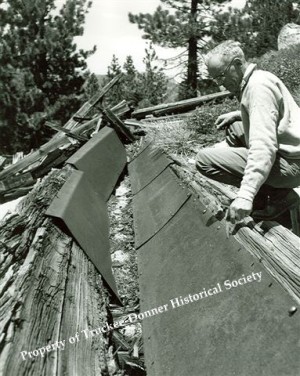

Gilman Folsom took on the task of dismantling the railroad, the sawmill and any other salvageable parts for the new mill. The incline stayed, but just about everything else was loaded onto barges and shipped over to Agate Bay, where it was loaded onto wagons. They even created a temporary town there called "Bay City".

The teamsters coaxed their oxen along as they hauled the heavy wagons over the summit, through the Martis Valley, stopped to quench their thirst in Truckee, then headed north to the new lumber camp of Overton.

By the end of 1897 Incline was a ghost town. The Washoe returned to claim the gardens, and the forests began to grow again. But the story wasn’t finished.

Building the New Town of Hobart Mills

In 1896 the machinery from Incline lays scattered around a large flat spot on the north side of Prosser Creek, some five miles north of Truckee. Tents were mostly in evidence, as the sawmill and town site were just being staked out.

A seven mile standard gauge railroad from Truckee was under construction, supervised by Captain John Bear Overton, the long time field general of the SNW&LC at Incline. Two standard gauge locomotives engines were at work building the new line, as were many of the loggers and millmen. The new town would be named Overton to honor his dedication to the company.

Overton, or Hobart Mills as it would soon become known, was laid out on the best modern engineering. It would still be Overton today if not for the Post Office denying that name as there were too many Overtons already in use. The streets were wide, they had excellent water pressure with fine pure mountain spring water, they had a modern for its time sewage system, electric lights, a fire department and all the requirements of a large isolated mountain town. The construction work was well supervised by Ab Spencer, who was a master at his trade.

No Stranger to Lumbering

The immediate area around Hobart Mills was no stranger to lumbering. The flat area below the town was named Katz’s Flat for Fred Katz, a logger of the 1870s who logged the Prosser Creek timber up to just above Hobart Mills.

A reservoir had been built downstream from Hobart Mills by Gilman Folsom when he was partners in the Pacific Lumber & Wood Company at Clinton below Boca. That provided a head of water for Katz’s logs that were floated down Prosser Creek and the Truckee River to the sawmill.

Just upstream from Hobart Mills was the Nevada & California sawmill, built by Seth Martin in 1872, but owned and run by Oliver Lonkey of the Verdi Lumber Company. A V flume from this mill, plus a flume from the Banner Mill on Sagehen Creek passed right by the new town. This mill was still running while Overton was being built, and may have provided some of the lumber for the first houses.

The land that Hobart had bought came from a variety of sources. He bought Central Pacific Railroad checkerboard land grant lands, U.S. government lands, from other lumber companies, with Civil War veteran land scrip, from homesteaders and timber claims from individuals, and later buying timber from Forest Service.

William Tiffany

The man who gets the credit for putting together some 70,000 acres of virgin pine and fir timberlands was William B. Tiffany. Tiffany was an experienced lumber and wood man who run his own operation in the Truckee River Canyon below Floriston in the 1870s. Hobart hired him to cruise timber, survey land lines, measure water resources, and buy the land ahead of others. He had a head for figures, rarely wrote much down but could remember the smallest detail.

Tiffany spent years hiking the forests of Lake Tahoe, but especially had centered on the lands north of Truckee from Alder Creek, Prosser Creek, Sagehen Creek, Independence Lake, Webber Lake, almost to Sierraville and to the east to Stampede and Sardine Valleys. The forests contained over 1.5 billion board feet of lumber and millions of cords of wood.

The Hobart’s plans had always been to hold off logging these thick forests until other lumberman had cut off the easy timber and the prices had risen. Both Hobart Sr. and Jr. understood the organization and attention to detail that was required to build and run such a large operation and make a profit.

A Great Enterprise

The fury of activity at Hobart Mills in 1896 was impressive. The railroad broke ground on July 6, and was completed to Overton on September 7. A 1,000 foot wooden trestle, later replaced by concrete and steel, was built over Prosser Creek, right over the reservoir created by Gilman Folsom 25 years before. The concrete foundations from this bridge remain at the upper end of Prosser Creek Reservoir.

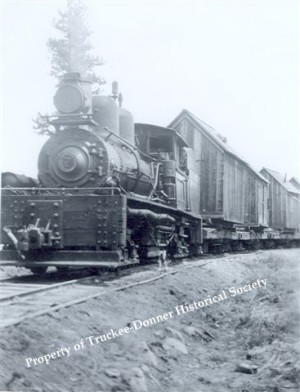

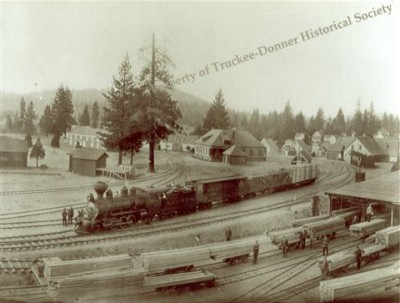

By the October of 1896, George Giffen was making daily trips on the new line. Work on the narrow gauge logging line that ran into the forests was also under construction, utilizing the former Incline rails and locomotives. Giffen had the honor of running the former Virginia & Truckee RR’s locomotive, the J.W. Bowker. This Baldwin built locomotive had been hauling the lumber of the SNW&LC for years when the company had been landing its wood products at Lakeview Station, the end the long flume from Incline.

The Bowker is still around, having been preserved rather than scrapped. It was a Hollywood favorite, having been used in 1939 for the filming of De Mille’s classic Union Pacific. It also starred in the movie version of The Wild Wild West, and is now in the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento.

Work on the sawmill commenced on September 20, and was started up on July 31, 1897. The saws were set up to cut 130,000 board feet a day, a huge amount for the time, and additional capacity was soon added. This was industrial logging and lumber production on a immense scale, far bigger than the Incline operation.

The large logs were run through a band saw capable of slicing a seven foot diameter log. Smaller logs were cut directly on circular saws, with both followed by gang saws that cut the lumber into one or two inch thick boards. Further trimming produced strong high quality lumber.

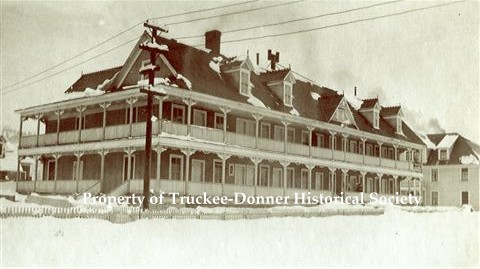

Hobart Inn Visitors to the sawmill and factory were constant. It became a popular part of mountain vacations to stop for a night at Hobart Mills Hotel, and tour the town. A catwalk carried a visitors gallery over the whirring saws, providing an excellent view. Guests were amazed at the speed and efficiency that logs were turned into lumber.

Working as a contractor was veteran Tahoe-Truckee lumberman Gilman Folsom, who had been a partner in a sawmill at Clinton below Boca from 1870 to 1880. In 1880 Folsom partnered with Sam Marlette and they took up a 40,000 cord a year wood cutting contract that employed over 400 men year round, and starting contract logging for the company the following year.

The company also hired Chinese workers, mostly for menial tasks and most of the wood cutting. As Truckee area lumbermen were being boycotted by white laborers for hiring Chinese workers and were responding by firing the Chinese, SNW&L took the opposite approach and hired more Chinese and fired the whites. While the whites were laid off in winter, the Chinese cut firewood in the mountains throughout the fiercest storms the Carson Range could offer.

By 1883 SNW&LC owned 70,000 acres north of Truckee in the Prosser, Sagehen Creek and Little Truckee River. Rumors constantly circulated around Truckee in the 80s and early 90s that Hobart was going to buy an existing sawmill or build a new one and start logging these forests.

While the Carson Range lands were the center of Lake Tahoe operations, Walter Hobart continued to invest in timberlands on the north and west shores of Tahoe. Enough timber had been purchased to last almost to 1900 if all went according to plan. The future looked bright.

Land of Lumber and Fertile Soil

The village of Incline, the sole owner and business being the SNW&LC, had applied for a post office upon moving to lake Tahoe from Little Valley in 1880. It took four years for the Post Office to grant a fourth class office with Gilman Folsom as Postmaster. The village near the mill, containing a store, a boardinghouse, a stable and a few cabins also had daily steamer service in the summer and weekly in the winter. Now it was on the map.

Winter was tough on the men and the company, with most of the work stopping and the mill closing down after the last logs were cut. Woodcutting continued through storms or blue skies. Most of the loggers and millmen spent the winter on ranches in the Nevada valleys. In the winter of 1884 a mile of V flume on a trestle some 80 feet high, was blown down up in Little Valley, but was rebuilt in the snow in only eight days.

By 1884 Gilman Folsom was cutting sawlogs on the southeast shore of Lake Tahoe. These logs and others from around Lake Tahoe were rolled into the lake, cabled together to form rafts and towed by the steamboat Niagra to Sand Harbor. The log landing at Incline was too sandy and unprotected, so Sand Harbor was chosen for the log landing. There the logs were pulled by steam engine onto narrow gauge flatcars that were hauled back to the sawmill by a wood fired locomotive.

Surprisingly the area around Incline, with its mild climate and good soil was a garden spot. SNW&LC had acres of gardens that solved the problem of shipping in fresh food from the Carson and Washoe Valleys. They grew potatoes, onions, lettuce, corn, cabbage, turnips, radishes, and several acres of grain and hay for animal feed.

The Washoe Connection

When the grain field was first cleared, it was early in the spring, and just as they were ready to plant, Captain Joe, Chief of the Washoe, came to Gilman Folsom and told a tale of woe.

Once, all this was land was ours. We killed the deer and bear all over the mountains. When the white man came and took away all our land, except this one little spot, where the creek comes down the mountain. Here we came to camp and hunt rabbits and catch fish. Here we lived every summer and we buried our dead. Now you want to take this one last little resting place from us.

Folsom and part owner Sam Marlette were too tender hearted to resist the pleadings of the eloquent children of the forest and so they abandoned the field, and moved uphill a mile away where they cleared another field for grain. That pleased the Washoe it seemed, at least for that season.

The following year however, Captain Joe was willing to forego his ancestral summer home for a $20 gold piece. Both fields were then planted to feed the hungry lumbermen.

Another of the Truckee area lumbermen who were attracted to the quality operations being run by Hobart & Marlette was James "Nat" Durney. Durney sold his Truckee grocery store in 1884 so he could manage the general merchandise business in Incline.

This deal was worked out because Sisson Crocker Company, who had operations all over the western forests, had contracted to run all of Hobart’s woods crews and Durney was managing that operation as well. After a few years saving his money, Durney moved on to own his own sawmills and stores and was a millionaire by 1910.

Looking for a Blowout

SNW&LC kept a fairly tight rein on alcohol in the company owned town. Still a man needed to blow off steam and the upscale Tahoe resorts didn’t appreciate their hard earned money. A few backwoods dives with watered down tarantula juice could quench that thirst after work, but for a real good time the men rode over to Truckee and kept that town and sometimes its jails quite lively. The biggest Truckee shindig was when the season ended, and all the workingmen descended on the dozens of saloons and the Jibboom Street brothels with the seasons wages in their pockets.

Fire was always a fear in the sawmill, as the combination of dry sawdust and kerosene lamps caused disaster when they came together. So it was no surprise that on June 21, 1886, Captain Overton received a telegram in Virginia City telling him the mill was on fire. As with most sawmills, there was inadequate water supply and mill went up in flames.

Even though timber was becoming depleted, and Virginia City mining had dwindled to a trickle, the sawmill was quickly rebuilt and new machinery installed. Lumber production of

Rails by the Lakeshore

By the mid 1880s lumbermen all over the West were turning to narrow gauge railroads to move sawlogs through the mountains. Hobart & Marlette were no exception. In 1881 they built a two mile spur that ran from the mill to the west towards the California state line. They even designed a new style of logging railcar axles, one that had coupling in the middle, so the log cars could go around sharp corners easier.

In 1888 they started extending the rails south to Sand Harbor, completing it the following year. This allowed them to use that protected bay for unloading log rafts. The log trains rumbled along the lakeshore on a shelf carved out of the rocks above the lake, a route that would eventually become Highway 28.

With Charley Blethen running the original locomotive, a second engine was added in June of 1889 to the Sand Harbor run. The new rail line and additional locomotive was the result of the reduction of timber cutting around Crystal Bay and Folsom’s opening of new logging operations near Zephyr Cove on the southeast corner of the lake. Folsom even named his new town Hobart to keep on the good graces of Walter Hobart.

Throughout the early 90s logging and wood cutting continued full force. The steamer Niagra made frequent trips towing logs from Zephyr Cove to Sand Harbor. And the incline and flume were taxed to full capacity to keep up demand for lumber. The markets had changed with the times, instead of supplying strictly Virginia City, they were shipping lumber throughout the West.

All this despite the death of Walter Hobart Sr. in June of 1892, but his son Walter Jr. took over the management, assisted by a corps of lawyers and advisers. The $800,000 estate included the untouched timberland north of Truckee. It was only a matter of timing to start the relocation.

By the end of 1893 timber was scarce and operations began to wind down. In 1894 they sold the flume to the Carson & Tahoe Lumber Company, the Bliss controlled lumber operation at Glenbrook, that was itself starting to see the end of logging on the horizon. The move was accelerated by a trade of 5,000 acres of timberland that SNW&LC owned between Lake Tahoe & Truckee, to the Truckee Lumber Company who gave an equal amount over north of Truckee, adjacent to the lands that had been bought by Hobart 20 years earlier.

1895 was a year of preparation, as the last of lumber and firewood was shipped, and a crew of surveyors and engineers looked over the land north of Truckee for a new mill site. They soon narrowed down the sites to a flat glacial outwash just north of Prosser Creek, miles north of Truckee.

Gilman Folsom took on the task of dismantling the railroad, the sawmill and any other salvageable parts for the new mill. The incline stayed, but just about everything else was loaded onto barges and shipped over to Agate Bay, where it was loaded onto wagons. They even created a temporary town there called "Bay City".

The teamsters coaxed their oxen along as they hauled the heavy wagons over the summit, through the Martis Valley, stopped to quench their thirst in Truckee, then headed north to the new lumber camp of Overton.

By the end of 1897 Incline was a ghost town. The Washoe returned to claim the gardens, and the forests began to grow again. But the story wasn’t finished.

Building the New Town of Hobart Mills

In 1896 the machinery from Incline lays scattered around a large flat spot on the north side of Prosser Creek, some five miles north of Truckee. Tents were mostly in evidence, as the sawmill and town site were just being staked out.

A seven mile standard gauge railroad from Truckee was under construction, supervised by Captain John Bear Overton, the long time field general of the SNW&LC at Incline. Two standard gauge locomotives engines were at work building the new line, as were many of the loggers and millmen. The new town would be named Overton to honor his dedication to the company.

Overton, or Hobart Mills as it would soon become known, was laid out on the best modern engineering. It would still be Overton today if not for the Post Office denying that name as there were too many Overtons already in use. The streets were wide, they had excellent water pressure with fine pure mountain spring water, they had a modern for its time sewage system, electric lights, a fire department and all the requirements of a large isolated mountain town. The construction work was well supervised by Ab Spencer, who was a master at his trade.

No Stranger to Lumbering

The immediate area around Hobart Mills was no stranger to lumbering. The flat area below the town was named Katz’s Flat for Fred Katz, a logger of the 1870s who logged the Prosser Creek timber up to just above Hobart Mills.

A reservoir had been built downstream from Hobart Mills by Gilman Folsom when he was partners in the Pacific Lumber & Wood Company at Clinton below Boca. That provided a head of water for Katz’s logs that were floated down Prosser Creek and the Truckee River to the sawmill.

Just upstream from Hobart Mills was the Nevada & California sawmill, built by Seth Martin in 1872, but owned and run by Oliver Lonkey of the Verdi Lumber Company. A V flume from this mill, plus a flume from the Banner Mill on Sagehen Creek passed right by the new town. This mill was still running while Overton was being built, and may have provided some of the lumber for the first houses.

The land that Hobart had bought came from a variety of sources. He bought Central Pacific Railroad checkerboard land grant lands, U.S. government lands, from other lumber companies, with Civil War veteran land scrip, from homesteaders and timber claims from individuals, and later buying timber from Forest Service.

William Tiffany

The man who gets the credit for putting together some 70,000 acres of virgin pine and fir timberlands was William B. Tiffany. Tiffany was an experienced lumber and wood man who run his own operation in the Truckee River Canyon below Floriston in the 1870s. Hobart hired him to cruise timber, survey land lines, measure water resources, and buy the land ahead of others. He had a head for figures, rarely wrote much down but could remember the smallest detail.

Tiffany spent years hiking the forests of Lake Tahoe, but especially had centered on the lands north of Truckee from Alder Creek, Prosser Creek, Sagehen Creek, Independence Lake, Webber Lake, almost to Sierraville and to the east to Stampede and Sardine Valleys. The forests contained over 1.5 billion board feet of lumber and millions of cords of wood.

The Hobart’s plans had always been to hold off logging these thick forests until other lumberman had cut off the easy timber and the prices had risen. Both Hobart Sr. and Jr. understood the organization and attention to detail that was required to build and run such a large operation and make a profit.

A Great Enterprise

The fury of activity at Hobart Mills in 1896 was impressive. The railroad broke ground on July 6, and was completed to Overton on September 7. A 1,000 foot wooden trestle, later replaced by concrete and steel, was built over Prosser Creek, right over the reservoir created by Gilman Folsom 25 years before. The concrete foundations from this bridge remain at the upper end of Prosser Creek Reservoir.

By the October of 1896, George Giffen was making daily trips on the new line. Work on the narrow gauge logging line that ran into the forests was also under construction, utilizing the former Incline rails and locomotives. Giffen had the honor of running the former Virginia & Truckee RR’s locomotive, the J.W. Bowker. This Baldwin built locomotive had been hauling the lumber of the SNW&LC for years when the company had been landing its wood products at Lakeview Station, the end the long flume from Incline.

The Bowker is still around, having been preserved rather than scrapped. It was a Hollywood favorite, having been used in 1939 for the filming of De Mille’s classic Union Pacific. It also starred in the movie version of The Wild Wild West, and is now in the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento.

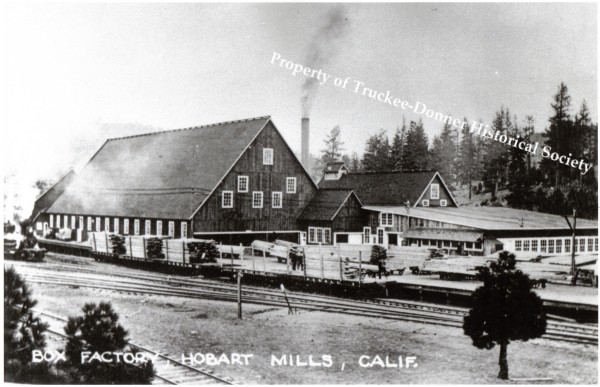

Work on the sawmill commenced on September 20, and was started up on July 31, 1897. The saws were set up to cut 130,000 board feet a day, a huge amount for the time, and additional capacity was soon added. This was industrial logging and lumber production on a immense scale, far bigger than the Incline operation.

The large logs were run through a band saw capable of slicing a seven foot diameter log. Smaller logs were cut directly on circular saws, with both followed by gang saws that cut the lumber into one or two inch thick boards. Further trimming produced strong high quality lumber.

Hobart Inn Visitors to the sawmill and factory were constant. It became a popular part of mountain vacations to stop for a night at Hobart Mills Hotel, and tour the town. A catwalk carried a visitors gallery over the whirring saws, providing an excellent view. Guests were amazed at the speed and efficiency that logs were turned into lumber.

|

The largest amount of rough lumber was planed into fine finished pine lumber, and most of that was used to make wooden boxes. In the days before cardboard and plastic, just about everything was shipped in wooden boxes. The majority of the boxes were used in the California agriculture business, for shipping fresh citrus fruits and vegetables east on the railroads. An example is an order from Southern California for 999,000 orange boxes, that filled 222 railcars, and took 111 days to fill.

|

Other portions of the massive factory that ran year round were used to produce doors, windows, paneling, flooring, and a variety of finished furniture.

A separate small sawmill was in use logging off Alder Creek from 1901 to 1904. It was connected to the Hobart standard gauge railroad by a two mile spur. In addition to logging pine for lumber, white and red fir were cut into four foot lengths, split and cured in piles out in the forests. When dry, the wood was transported to the Floriston Paper mill. |

Green Power

The sawmill and factory complex was powered by a self feeding sawdust and wood scrap fired steam plant whose five boilers powered two steam engines that ran the machinery and the electric plant. The larger of the two engines was named Beast, while the smaller was called Beauty.

Water for the boilers, sawmill, and town came from Hobart Reservoir, located a half mile to the north. It was fed by a three mile pipeline from Sagehen Creek. The reservoir supplied 120 pounds of pressure, enough so that water turbines were used to power small direct current electric lights and machinery.

A huge field of piled lumber was always drying in the flat to the south, and wood fired dry kilns cured the lumber to perfection. One of the first large shipments out of the yards didn’t go very far. Three million feet were sent to Floriston in 1899 & 1900 to build the town and the Floriston Paper Mill.

But after that, pine lumber was shipped all over the West, and regularly to the east coast. Sailing and steam ships took shiploads of it across the Pacific Ocean, such was the demand for Sierra Pine.

Looking for a Good Time

Saloons were banned in Hobart Mills, as were liquor sales at the company owned Overton Mercantile, but across Prosser Creek was Klondike where first J.B.Welton, then the McLeods, ran a small roadhouse on one of the few properties not controlled by the company. Still, those who overindulged were met with stern warnings and then dismissal if they persisted on excessive drinking.

When the woodsmen came in from the logging camps, they weren’t as concerned about being civilized, so they went on to Truckee where they had their choice of saloons and entertainment. The town was so well behaved, that at least up until 1900 the company found "no need for a Constable or a Justice of The Peace", while Truckee struggled to fight crime with four officers.

While there was no church in Hobart Mills, worshipers attended services in Truckee, or at times the Truckee Methodist ministers and Catholic priests would hold services at Hobart Mills. Management’s goal was to keep the working men too busy to drink or pray.

A Small City

The town was originally built for 1000 people, almost as large as Truckee was in 1897, and with additional housing, grew to house over 1500 people at times. It cost over $250,000 to build to the town and the lumber works, with the whole property worth $2,000,000 in 1900 prices.

For employee accommodations, SNW&LC provided a clean place to live with good meals, for a reasonable price. Single men stayed in the hotel, bunkhouses, or in the boarding house. The married men had nice small houses on the neat streets, with children playing in the yards. The company persuaded as many men as possible to get married, raise families, and made sure they were rewarded for living a productive sober life.

Even with plenty of wood framed houses for those who held they better positions, two suburbs of Hobart Mills grew with the town. Ragtown, just to the southwest was named that because it was a tent city in the summer, but after a long summer, some of the white tents looked more like rags. Flumeville, named for the remains of the abandoned Lonkey lumber flume, was built by scavengers ripping apart the flume and building shacks out of the lumber. As more permanent housing was built, both of these villages ceased to exist.

Proud of Their School

In 1898 the new schoolhouse was built on the northwest side of town. A time capsule was placed in the rocks of the foundation. This was recovered during the 1967 by Pat McKendry, who in 2006 donated it to the Truckee District of the Tahoe National Forest. It contained various newspapers of 1897 and ‘98, descriptions of Hobart Mills, documents that listed the Schoolteacher, the first 20 students, and the School Board Trustees. Townsfolk were proud of their school and pushed the children to graduate and go to High School in Truckee.

There were clubs for the women and children and the social clubs of Truckee welcomed Hobart people. Various clubs were formed, such as a band club, dramatic club, dance classes, Pine Burr club, the Anti-Fats a walking club, sewing club, auto club, and the most popular and longest lasting, the Housekeepers Club. sled

Even though the company stressed safety and cleanliness, accidents occurred and people got sick. So by 1900 the Hobart Hospital was open and staffed by a nurse. Dr. Nahl was hired soon after, and after that until the mill’s closure, a doctor was on staff to deal with the many injuries. Other operations were performed, and people from Truckee were treated at times, since Truckee didn’t have a hospital after 1910.

More than Lumber

One of the key resources that Hobart also had Tiffany buying up with timberlands was the water rights of the creeks that flowed through the mountains. Long before 1897, Hobart was actively defending those water rights, such as in August of 1877, when the gates on the Prosser Creek dam for the Lonkey’s mill were closed and guarded under watch of rifle toting guards.

This closure forced the closure of the Nevada & California sawmill, with Hobart threatening to blow up the dam unless Lonkey paid for the water rights. The matter was quickly resolved without gunfire or extensive legal wrangling.

SNW&LC also bought the water rights to Webber Lake and Independence Lake from the Boca Lumber Company. As water demand increased in Nevada, these reservoirs would bring a large profit to the company as they sold the water in dry years to the highest bidder.

Hobart also bought the resort at Independence Lake, leasing the popular summer resort to Mrs. Clemmons until 1917 when Mrs. Kenney leased it. Vacationers and Hobart Mills employees often spent summer weekends fishing and boating on the beautiful mountain lake.

Once the forest was logged, the openings sprouted new grass and sun loving plants. The cut over land was excellent grazing land for sheep and cattle. SNWL leased this land for grazing at a healthy profit. Those who trespassed, such as the three Flanigan brothers in 1897, were promptly arrested, their sheep herd ran off, the brothers and were fined $15 each.

The Best People

The Hobarts believed in hiring the best people available and building loyalties that would last for generations. One example is the Charles Barton, who started as a logging contractor for SNW&LC in 1883 at Incline, and was logging in the Hobart Mills forests by 1899. He brought along his sons Charles Jr. and Oren, who was a locomotive engineer for several decades.

Barton would continue logging until 1907, then went to run Corey’s Station, a small company owned roadhouse, for another decade. The way station was located about five miles north of Hobart Mills on the old Sierraville stage road.

The sawmill and factory complex was powered by a self feeding sawdust and wood scrap fired steam plant whose five boilers powered two steam engines that ran the machinery and the electric plant. The larger of the two engines was named Beast, while the smaller was called Beauty.

Water for the boilers, sawmill, and town came from Hobart Reservoir, located a half mile to the north. It was fed by a three mile pipeline from Sagehen Creek. The reservoir supplied 120 pounds of pressure, enough so that water turbines were used to power small direct current electric lights and machinery.

A huge field of piled lumber was always drying in the flat to the south, and wood fired dry kilns cured the lumber to perfection. One of the first large shipments out of the yards didn’t go very far. Three million feet were sent to Floriston in 1899 & 1900 to build the town and the Floriston Paper Mill.

But after that, pine lumber was shipped all over the West, and regularly to the east coast. Sailing and steam ships took shiploads of it across the Pacific Ocean, such was the demand for Sierra Pine.

Looking for a Good Time

Saloons were banned in Hobart Mills, as were liquor sales at the company owned Overton Mercantile, but across Prosser Creek was Klondike where first J.B.Welton, then the McLeods, ran a small roadhouse on one of the few properties not controlled by the company. Still, those who overindulged were met with stern warnings and then dismissal if they persisted on excessive drinking.

When the woodsmen came in from the logging camps, they weren’t as concerned about being civilized, so they went on to Truckee where they had their choice of saloons and entertainment. The town was so well behaved, that at least up until 1900 the company found "no need for a Constable or a Justice of The Peace", while Truckee struggled to fight crime with four officers.

While there was no church in Hobart Mills, worshipers attended services in Truckee, or at times the Truckee Methodist ministers and Catholic priests would hold services at Hobart Mills. Management’s goal was to keep the working men too busy to drink or pray.

A Small City

The town was originally built for 1000 people, almost as large as Truckee was in 1897, and with additional housing, grew to house over 1500 people at times. It cost over $250,000 to build to the town and the lumber works, with the whole property worth $2,000,000 in 1900 prices.

For employee accommodations, SNW&LC provided a clean place to live with good meals, for a reasonable price. Single men stayed in the hotel, bunkhouses, or in the boarding house. The married men had nice small houses on the neat streets, with children playing in the yards. The company persuaded as many men as possible to get married, raise families, and made sure they were rewarded for living a productive sober life.

Even with plenty of wood framed houses for those who held they better positions, two suburbs of Hobart Mills grew with the town. Ragtown, just to the southwest was named that because it was a tent city in the summer, but after a long summer, some of the white tents looked more like rags. Flumeville, named for the remains of the abandoned Lonkey lumber flume, was built by scavengers ripping apart the flume and building shacks out of the lumber. As more permanent housing was built, both of these villages ceased to exist.

Proud of Their School

In 1898 the new schoolhouse was built on the northwest side of town. A time capsule was placed in the rocks of the foundation. This was recovered during the 1967 by Pat McKendry, who in 2006 donated it to the Truckee District of the Tahoe National Forest. It contained various newspapers of 1897 and ‘98, descriptions of Hobart Mills, documents that listed the Schoolteacher, the first 20 students, and the School Board Trustees. Townsfolk were proud of their school and pushed the children to graduate and go to High School in Truckee.

There were clubs for the women and children and the social clubs of Truckee welcomed Hobart people. Various clubs were formed, such as a band club, dramatic club, dance classes, Pine Burr club, the Anti-Fats a walking club, sewing club, auto club, and the most popular and longest lasting, the Housekeepers Club. sled

Even though the company stressed safety and cleanliness, accidents occurred and people got sick. So by 1900 the Hobart Hospital was open and staffed by a nurse. Dr. Nahl was hired soon after, and after that until the mill’s closure, a doctor was on staff to deal with the many injuries. Other operations were performed, and people from Truckee were treated at times, since Truckee didn’t have a hospital after 1910.

More than Lumber

One of the key resources that Hobart also had Tiffany buying up with timberlands was the water rights of the creeks that flowed through the mountains. Long before 1897, Hobart was actively defending those water rights, such as in August of 1877, when the gates on the Prosser Creek dam for the Lonkey’s mill were closed and guarded under watch of rifle toting guards.

This closure forced the closure of the Nevada & California sawmill, with Hobart threatening to blow up the dam unless Lonkey paid for the water rights. The matter was quickly resolved without gunfire or extensive legal wrangling.

SNW&LC also bought the water rights to Webber Lake and Independence Lake from the Boca Lumber Company. As water demand increased in Nevada, these reservoirs would bring a large profit to the company as they sold the water in dry years to the highest bidder.

Hobart also bought the resort at Independence Lake, leasing the popular summer resort to Mrs. Clemmons until 1917 when Mrs. Kenney leased it. Vacationers and Hobart Mills employees often spent summer weekends fishing and boating on the beautiful mountain lake.

Once the forest was logged, the openings sprouted new grass and sun loving plants. The cut over land was excellent grazing land for sheep and cattle. SNWL leased this land for grazing at a healthy profit. Those who trespassed, such as the three Flanigan brothers in 1897, were promptly arrested, their sheep herd ran off, the brothers and were fined $15 each.

The Best People

The Hobarts believed in hiring the best people available and building loyalties that would last for generations. One example is the Charles Barton, who started as a logging contractor for SNW&LC in 1883 at Incline, and was logging in the Hobart Mills forests by 1899. He brought along his sons Charles Jr. and Oren, who was a locomotive engineer for several decades.

Barton would continue logging until 1907, then went to run Corey’s Station, a small company owned roadhouse, for another decade. The way station was located about five miles north of Hobart Mills on the old Sierraville stage road.

Many other veteran lumbermen from all over the region worked at Hobart one time or another, including George Chubbuck, Robert Gracey, Levi Warren, John Duffy, C.R. "Roddy" McLellan, Howard Batchelder and the Boyington Brothers.

When manager J.B. Overton retired in 1900, after fulfilling his agreement to get the new town operating, he was replaced by a veteran Tahoe lumber manager, Charles T. Bliss, formerly of the Glenbrook sawmill operation. Stepping up to superintendent was George D. Oliver. Oliver would move up to manager in 1914 when Bliss left, and he would successfully guide the company and town through the rest of its life.

Web of Iron

To move the logs from the forests, first oxen and horses, then steam powered donkey engines skidded them to landings. The logs were loaded onto three foot gauge flatcars where a Shay geared engine would take them off the mountain. The light geared locomotive could climb steep grades, turn corners and just about climb the tree itself, allowing for rails to be built into the far corners of the Hobart forests.

When manager J.B. Overton retired in 1900, after fulfilling his agreement to get the new town operating, he was replaced by a veteran Tahoe lumber manager, Charles T. Bliss, formerly of the Glenbrook sawmill operation. Stepping up to superintendent was George D. Oliver. Oliver would move up to manager in 1914 when Bliss left, and he would successfully guide the company and town through the rest of its life.

Web of Iron

To move the logs from the forests, first oxen and horses, then steam powered donkey engines skidded them to landings. The logs were loaded onto three foot gauge flatcars where a Shay geared engine would take them off the mountain. The light geared locomotive could climb steep grades, turn corners and just about climb the tree itself, allowing for rails to be built into the far corners of the Hobart forests.

Once on the main line, a regular rod engine would speed it on its way to the log pond. The first rail lines went up Prosser Creek then later extensions went north to Sagehen Creek, and the Little Truckee River. Mileage varied from season to season, with as much as 25 miles in operation at one time. These narrow gauge lines only operated during the summer logging season.

The SNW&LC used up to five narrow gauge engines, with one of the three Shays, No.9 being added in 1913. This locomotive, like the J.W. Bowker, survived the closing in 1936, thanks to George Oliver, and it lives on, still running the rails of Yosemite Mountain & Sugar Pine Railroad near Yosemite.

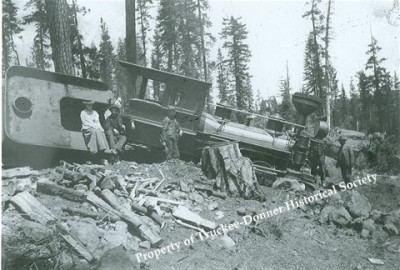

The shay geared locomotives normally hauled logs on the steeper backwoods rail lines. Here Shay #7 hauls a trainload of cabins from one logging camp to a new one.

The SNW&LC used up to five narrow gauge engines, with one of the three Shays, No.9 being added in 1913. This locomotive, like the J.W. Bowker, survived the closing in 1936, thanks to George Oliver, and it lives on, still running the rails of Yosemite Mountain & Sugar Pine Railroad near Yosemite.

The shay geared locomotives normally hauled logs on the steeper backwoods rail lines. Here Shay #7 hauls a trainload of cabins from one logging camp to a new one.

Hobart Mills continued as a town, a society, and a lumber mill until 1936. With the virgin timber cut off, slowly salvaged and sold the remaining structures over the next few years, ending over 60 years of the Hobart lumber empire. The Hobart Mills forests, still thriving with second growth trees were sold to the US Forest Service, and the 21,000 acres of Incline lands to George Whittell.

The forests of the Lake Tahoe and Truckee provided the lumber needed to develop the natural resources of the West for 60 years. As time goes by, the scars of this great enterprise vanish and only the history remains.

The forests of the Lake Tahoe and Truckee provided the lumber needed to develop the natural resources of the West for 60 years. As time goes by, the scars of this great enterprise vanish and only the history remains.