C-47D Airplane Crash near Independence Lake – “Rafferty’s Bell”

By Heidi Sproat

Researching the March 1946 aircraft crash of the C-47 just south of Hobart Mills and north of Truckee (see “On Wings of Terror” TDHS EFTP March 2016, pp. 6-7), (KCRW = Killed in a CRash due to Weather), I came across yet another very sad story about an airplane crash, ironically, also not far from Hobart Mills.

On October 26, 1950, a USAF Douglas C-47D Serial Number #43-49030 was flying on a military IFR flight from Hill Field AFB in Ogden, Utah, to McClellan AFB in Sacramento, CA. It disappeared and failed to report in. Search and rescue was employed but after 1500 hours flying time to locate the downed plane, it was not located until 7 months later, on May 31, 1951, near Carpenter Ridge at Independence Lake, Nevada County, California.1

In September 2010, Joe Idoni, a photo hiking journalist, captured photos of the C-47D crash site. Several of Idoni’s photos posted at his photo journal link are of incredible detail – and haunting. (See 2 photos below). The plane’s cargo included large heavy coils of telephone wires which had been anchored down by nylon webbing to insure they were securely fastened – just in case the plane encountered inclement weather.

After examining the plane’s wreckage, investigators could not find any evidence of material failure or malfunction. The crash report 2 suggests that it was pilot error failing to clear the mountain range thinking they had crossed them. Four men were killed in the crash. The crash was labelled KCRCG = Killed in CRash Ground Collision = “Where pilot flew plane into water, ground or mountain, not due to stall/spin, fire, structural failure, mid-air collision, engine failure, etc., aka CFIT.” The crash report further stated that the aircraft hit a rocky precipice head on.

The pilot apparently believed he was much further west of his position that he really was and sadly commenced a descent to McClellan AFB - when he had not yet cleared the Sierra Nevada mountains. Due to unusual radio static and lack of reception, radio communications were unreliable, and speculation is that the Donner Summit radio beacon could not be heard aboard the aircraft. With the strong headwinds, Pilot Rafferty apparently did not know his TRUE velocity. The pilot started a descent that he estimated put him well west of the 12,000 foot Donner Summit clearance marker. Sadly, he was mistaken.3 The pilot believed he was approaching the McClellan Beacon when in fact he had not yet crossed Donner Summit. The report also stated that there was a “probable venturi action of the terrain over which [the pilot] was flying immediately prior to [the] crash this his altimeter was indicating an altitude higher than he was actually flying.”4 The crash report concluded with a recommendation that the complete report be published in Flying Safety Magazine for information and guidance of all flying personnel. Further, that “the article should bear out the fact that pilots should not attempt descent under instrument conditions until their position has been definitely established.”

While I had seen references to this second crash in newspaper articles, it wasn’t until I saw Idoni’s images that I started to do further research. The wreckage that still remains visible – even after 70 years - is jarring. Note that about 100 feet below the top of the rock ledge is an abandoned cave, possibly used by early American Indians. Had the pilot flown 50 feet lower in altitude he may have flown directly into the cave. And had he flown only 200 feet higher, he would have been “home free.” This peakbagger map will also give you a good idea of the area’s mountainous terrain, as well as this Summit Post site; and this USGS site. In a gripping article by R.W. Koch, the writer explains that the propeller, interlaced amidst twisted telephone cables, would, in any strong breeze or wind, repeatedly clank on the sheer volcanic rock outcropping creating an eerie sound much like the “lonely bell buoy” to mark harbor entrances. A chilling sound, sometimes referred by the locals as “Rafferty’s Bell.”

As disturbing as the final demise of this plane is, the view eastward from this mountain top is a stunning panoramic. Independence Lake is 1,300 feet below. Mt. Lola stands 9,143 (9,147 per NGS site) feet high on the southwest side of the lake and the rest of the neighboring mountain range is 8,500 feet high. The crash site is at the 8,200 foot level of the 9,103 foot high mountain peak above the south side of the lake. (2018 hikers posted photos of Mt. Lola at this public link. This will also give you some idea of the ruggedness and isolation of the terrain. Just imagine flying IFR - at night - in 1950 - in a snowstorm - over this terrain.5 Terrifying.)

Here is one newspaper article about locating the plane’s wreckage.

On October 26, 1950, a USAF Douglas C-47D Serial Number #43-49030 was flying on a military IFR flight from Hill Field AFB in Ogden, Utah, to McClellan AFB in Sacramento, CA. It disappeared and failed to report in. Search and rescue was employed but after 1500 hours flying time to locate the downed plane, it was not located until 7 months later, on May 31, 1951, near Carpenter Ridge at Independence Lake, Nevada County, California.1

In September 2010, Joe Idoni, a photo hiking journalist, captured photos of the C-47D crash site. Several of Idoni’s photos posted at his photo journal link are of incredible detail – and haunting. (See 2 photos below). The plane’s cargo included large heavy coils of telephone wires which had been anchored down by nylon webbing to insure they were securely fastened – just in case the plane encountered inclement weather.

After examining the plane’s wreckage, investigators could not find any evidence of material failure or malfunction. The crash report 2 suggests that it was pilot error failing to clear the mountain range thinking they had crossed them. Four men were killed in the crash. The crash was labelled KCRCG = Killed in CRash Ground Collision = “Where pilot flew plane into water, ground or mountain, not due to stall/spin, fire, structural failure, mid-air collision, engine failure, etc., aka CFIT.” The crash report further stated that the aircraft hit a rocky precipice head on.

The pilot apparently believed he was much further west of his position that he really was and sadly commenced a descent to McClellan AFB - when he had not yet cleared the Sierra Nevada mountains. Due to unusual radio static and lack of reception, radio communications were unreliable, and speculation is that the Donner Summit radio beacon could not be heard aboard the aircraft. With the strong headwinds, Pilot Rafferty apparently did not know his TRUE velocity. The pilot started a descent that he estimated put him well west of the 12,000 foot Donner Summit clearance marker. Sadly, he was mistaken.3 The pilot believed he was approaching the McClellan Beacon when in fact he had not yet crossed Donner Summit. The report also stated that there was a “probable venturi action of the terrain over which [the pilot] was flying immediately prior to [the] crash this his altimeter was indicating an altitude higher than he was actually flying.”4 The crash report concluded with a recommendation that the complete report be published in Flying Safety Magazine for information and guidance of all flying personnel. Further, that “the article should bear out the fact that pilots should not attempt descent under instrument conditions until their position has been definitely established.”

While I had seen references to this second crash in newspaper articles, it wasn’t until I saw Idoni’s images that I started to do further research. The wreckage that still remains visible – even after 70 years - is jarring. Note that about 100 feet below the top of the rock ledge is an abandoned cave, possibly used by early American Indians. Had the pilot flown 50 feet lower in altitude he may have flown directly into the cave. And had he flown only 200 feet higher, he would have been “home free.” This peakbagger map will also give you a good idea of the area’s mountainous terrain, as well as this Summit Post site; and this USGS site. In a gripping article by R.W. Koch, the writer explains that the propeller, interlaced amidst twisted telephone cables, would, in any strong breeze or wind, repeatedly clank on the sheer volcanic rock outcropping creating an eerie sound much like the “lonely bell buoy” to mark harbor entrances. A chilling sound, sometimes referred by the locals as “Rafferty’s Bell.”

As disturbing as the final demise of this plane is, the view eastward from this mountain top is a stunning panoramic. Independence Lake is 1,300 feet below. Mt. Lola stands 9,143 (9,147 per NGS site) feet high on the southwest side of the lake and the rest of the neighboring mountain range is 8,500 feet high. The crash site is at the 8,200 foot level of the 9,103 foot high mountain peak above the south side of the lake. (2018 hikers posted photos of Mt. Lola at this public link. This will also give you some idea of the ruggedness and isolation of the terrain. Just imagine flying IFR - at night - in 1950 - in a snowstorm - over this terrain.5 Terrifying.)

Here is one newspaper article about locating the plane’s wreckage.

1 The Tahoe Donner Land Trust has a map which shows the proximity of Independence Lake and Carpenter Ridge where the crash site was described. Google Drive link showing proximity to Truckee.

2 I successfully obtained the Air Force's official Accident Report # 50-10-26-5 in February 2020, pp. 1679-1757 on CD #46748.

3 Master Sergeant William Rafferty was one of the last rated enlisted pilots in the USAF and had a reputation as an outstanding pilot. His home field at the time was McClellan AFB, Sacramento. [Koch]

4 Another accounting reported that “for unknown reasons the flight path was north of the airway course. It’s possible, because of the high terrain, that the radio beacon at Donner Summit could not be heard onboard the aircraft.” Possibly the pilot believed he was honing in on the McClellan beacon. (Macha and Jordan article)

5 IFR means Instrument Flight Rules, v. VFR, visual flight rules. IFR navigation is in reference to electronic signals by flight deck instruments vs. visual flight reference.

2 I successfully obtained the Air Force's official Accident Report # 50-10-26-5 in February 2020, pp. 1679-1757 on CD #46748.

3 Master Sergeant William Rafferty was one of the last rated enlisted pilots in the USAF and had a reputation as an outstanding pilot. His home field at the time was McClellan AFB, Sacramento. [Koch]

4 Another accounting reported that “for unknown reasons the flight path was north of the airway course. It’s possible, because of the high terrain, that the radio beacon at Donner Summit could not be heard onboard the aircraft.” Possibly the pilot believed he was honing in on the McClellan beacon. (Macha and Jordan article)

5 IFR means Instrument Flight Rules, v. VFR, visual flight rules. IFR navigation is in reference to electronic signals by flight deck instruments vs. visual flight reference.

(Above and below) From Joe Idoni’s photo collection of site visit, September 2010. Used with written permission.

References

Newspapers

Californian (The)

Folsom Telegraph

Hanford Sentinel (The)

Los Angeles Times (The)

San Francisco Examiner

AAIR (Aviation Archaeological Investigation & Research) Crash Report segments, courtesy of photo journalist Joe Idoni. USAAF/USAF Accident Report Monthly List. Specifically, October 1950 list.

Department of the Air Force Inspector General, USAF. Flying Safety. Washington, D.C., n. d.

Gero, David. Military Aviation disasters: Significant losses since 1908. Patrick Stephens Limited, Newbury Park, CA (1999).

Koch, R.W., “Rafferty’s Last Flight”. Published in Air Classics Magazine, V. 16, No. 3, March 1980.

Macha, Gary Patric and Jordan, Don. Aircraft Wrecks in the mountains and deserts of California, 1909-2002. Lake Forest, CA (2002). 3rd Ed.

Newspapers

Californian (The)

Folsom Telegraph

Hanford Sentinel (The)

Los Angeles Times (The)

San Francisco Examiner

AAIR (Aviation Archaeological Investigation & Research) Crash Report segments, courtesy of photo journalist Joe Idoni. USAAF/USAF Accident Report Monthly List. Specifically, October 1950 list.

Department of the Air Force Inspector General, USAF. Flying Safety. Washington, D.C., n. d.

Gero, David. Military Aviation disasters: Significant losses since 1908. Patrick Stephens Limited, Newbury Park, CA (1999).

Koch, R.W., “Rafferty’s Last Flight”. Published in Air Classics Magazine, V. 16, No. 3, March 1980.

Macha, Gary Patric and Jordan, Don. Aircraft Wrecks in the mountains and deserts of California, 1909-2002. Lake Forest, CA (2002). 3rd Ed.

UPDATE:

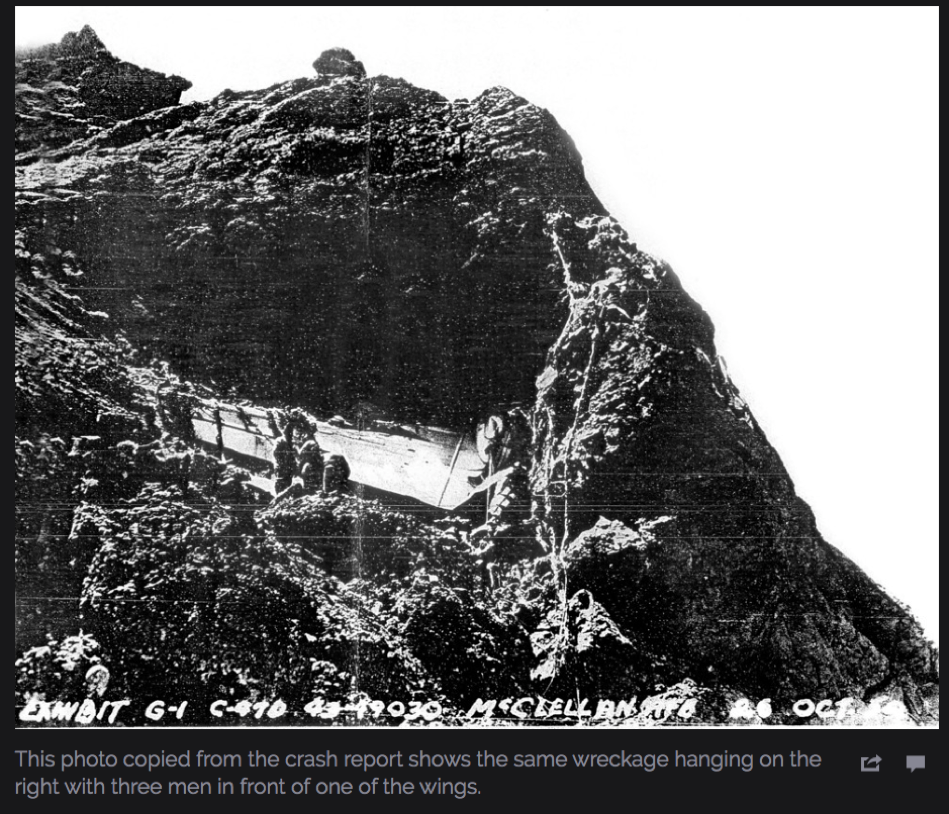

So, in just under 24 hours, an astute aviation researcher noticed our article about "Rafferty's Bell" and mentioned he had an image of the actual 1950 crash. Amazing. The photograph below is used with written permission, G.P. Macha Collection, www.aircraftwrecks.com . Mr. Macha also noted that there is an Air Force enlisted man standing just to the right of the tail. Thank you to our kind research donor!

So, in just under 24 hours, an astute aviation researcher noticed our article about "Rafferty's Bell" and mentioned he had an image of the actual 1950 crash. Amazing. The photograph below is used with written permission, G.P. Macha Collection, www.aircraftwrecks.com . Mr. Macha also noted that there is an Air Force enlisted man standing just to the right of the tail. Thank you to our kind research donor!

HCS 1/19/2020; revised 1/21/2020; 2/5/2020; 3/1/2020