History of the Truckee Area - by Guy Coates

|

History of the Truckee Area - By Guy H. Coates

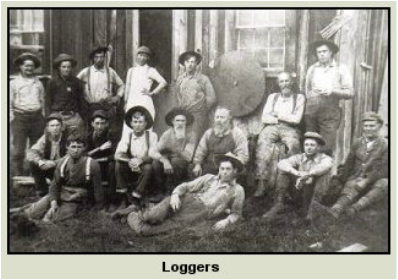

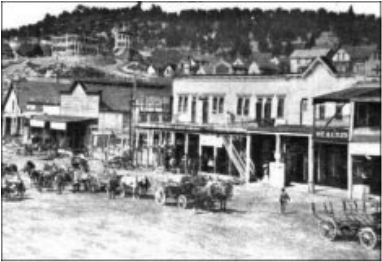

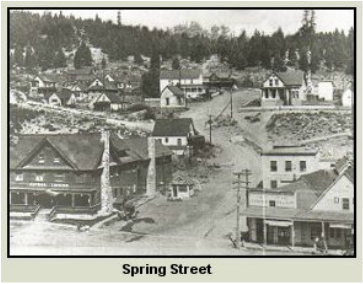

During the last three Ice Ages, glaciers covered the Truckee River basin and surrounding mountains carving out Donner Lake and many other lakes. Examining the smoothed and striated rock along old Highway 40 near Donner Pass, one can still see much evidence of this glacial action. To the east, today’s Nevada desert was covered by a huge inland sea. The earliest known inhabitants to occupy the Truckee area were prehistoric nomadic tribes who spent their winters in the Nevada desert and California valleys. During the summers these ancient hunters climbed both sides of the Sierra into the high country. These inhabitants, believed to be ancestors of the Washoe, Maidu and Paiute Indian Tribes, traveled through the pristine mountain meadows and forests collecting edible and medicinal roots, seeds and marsh plants. In the higher elevations they manufactured stone tools and hunted local game and fished in the many lakes and streams while living in temporary brush shelters. Archaeological evidence of these ancient people who returned year after year during the Middle Archaic Period can be found in petroglyphs carved into solid granite near the crest of Donner Summit as well as in the abundance of flaked stone artifacts, broken tools and dart points which have been discovered throughout the Truckee basin. The name of the town derives from a friendly Paiute Indian guide who, in 1844, assisted thousands of emigrants migrating west across the Humboldt Sink. The Indian’s name sounded like “Tro-kay” to the white men, who dubbed him “Truckee.” He became a favorite of the white settlers who found him to be honest and helpful. Chief Truckee fought bravely alongside Col. John C. Fremont in the Mexican War and was the father of Chief Winnemucca. In 1846 the Donner Party, consisting of 89 men, women and children followed a branch of the Emigrant trail known as the California Trail to the Truckee area in order to attempt a crossing of Donner Pass. They arrived in late October but the heavy snows had already begun, making it impossible to continue. Their fascinating story may be learned by visiting the Donner Memorial State Park, west of Truckee on Donner Pass Road, near the east end of Donner Lake. With the discovery of gold at Coloma in 1848 and silver in Virginia City in 1859, a road connecting the towns became imperative. The Dutch Flat-Donner Lake Wagon Road was built during this time and ran from present day Sacramento over Donner Summit and into Nevada. It became the primary route for freight wagons and passenger coaches headed for the mines in Virginia City. The first known white settlement in the Truckee basin was mentioned in the Nevada Transcript on April 20, 1866. Known as Pollard’s Station, it grew into a small township surrounding a hotel at the west end of Donner Lake. Not much is known about the hotel or its enterprising owner, J.D. Pollard, except that he was described as an affable man; an old hand at the hotel business who made sure his guests were never neglected. Stage coach stops were frequent and not far between over the mountain before the railroad. Pollard’s Station became an important stopping-off place for the California Stage Company’s stage coach line which connected Sacramento to the rich mines of Virginia City. In its heyday Pollard’s Station boasted two hotels, a general store and a sawmill. A glimpse of life at Pollard’s Station is outlined in The Journals of Alfred Doten, 1849-1903 Volume Two, published by the University of Nevada Press in 1973. On August 21, 1865. In the book, Doten recalls: “We left camp to take the stage as far as Donner Lake... terrifically dirty and dusty. We arrived at Donner Lake a little past 6 pm, heartily welcomed by Pollard. It is the principal station on the road with shops for repairing coaches, shoeing horses” After enjoying a round of cocktails with the stagecoach drivers, Eli Church and William Gearhart, Doten reflects on Mr. Pollard’s hospitality: “The table is well supplied with fish from the lake, and game from the hills, grouse, hare, eggs, milk. After supper we were in parlor awhile, chatting with Miss Kelsey and Miss Pollard. We sang them a song or two and passed an agreeable evening, and to bed at 12. Dan & I slept together on a big comfortable double bed. We rose at about 9 A.M. We had a good wash and clean up and put on a clean shirt.” Doten further observed “The hotel is beautifully situated on level place at head of the lake, surrounded and shaded with tall pines, tamaracks. The house is two stories high, large and roomy, with big 2 story L addition in back for a cook room, dining rooms, etc. below with sleeping rooms above. Everything about the house is fixed in comfortably elegant style. Quite a pleasure resort for visitors from Washoe and California.” Pollard’s hotel burned to the ground on April 23, 1867 and was rebuilt but later succumbed to another fire. Its few residents moved east to the new settlement at Coburn’s Station. The hotel was never again rebuilt because Pollard knew that once the railroad was built there would no longer be a need for the turnpike stages. By 1863 Joseph Gray had already constructed a log station along the wagon road at the intersection of today’s Jibboom and Bridge streets from which he provided provisions to the endless stream of freight wagons. He kept his corral full of cattle to provide fresh beef to teamsters and stored plenty of feed for their horses. Along with George Schaffer, Gray built a bridge across the Truckee River for which they charged a fee to cross. Henceforth his log cabin became known as Gray’s Toll Station. The cabin still exists, but has been moved to Church Street and currently is used as an office building. In 1865 a man named S.S. Coburn operated a stage station and public house for teamsters further west along the turnpike in today’s Brickelltown. Coburn himself was apparently a smith; an indispensable craftsman of the era who arrived from Dutch Flat with knowledge of the exact route of the proposed railroad. When the Central Pacific Railroad began their ascent into the Sierra Foothills, Coburn’s Station was selected as the advance camp for the railroad construction crews. Workmen poured into the area and the settlement grew overnight into a bustling lumber town. By December 1867, the first excursion train neared the summit. Despite severe winter storms a forty-ton locomotive named “San Mateo” was hauled in pieces on sleighs by George Schaffer and assembled near the site of today’s downtown depot. The engine was used to transport lumber from Schaffer’s Mill west to the summit where crews were laying track from both directions. On April 12, 1868, the Nevada City Daily Transcript announced: “The name ‘Coburn’s Station’ has been discarded by the people of that town and it is now called ‘Truckee.’ We learn from a correspondent that the post office has been discontinued at Donner Lake and a new one has been established at Truckee.” By the time the first train chugged through on June 9, 1868, the new town of Truckee encompassed the entire area opposite today’s C.B. White House along both sides of the tracks, including fifty buildings (mostly saloons), a hotel and twenty stores. Inevitably on the morning of July 30, 1868 a fire broke out opposite Campbell’s Tavern, destroying 50 buildings most of which were located on the south of the track. Many old timers insist that some of the homes in today’s Brickelltown were originally part of Coburn’s Station or built from lumber salvaged from partially burned buildings. There is archeological evidence that Truckee's first Chinatown existed along the hillside behind these homes. From the rubble of Coburn’s Station rose a new and bigger town, boasting nearly three hundred buildings, including twenty-five saloons, ten dry goods stores, eleven restaurants, a Central Pacific roundhouse, two theaters, two churches and a school house. The building of the railroad created what was then known as the second largest Chinatown on the Pacific Coast. Although essential to the railroad construction, the Chinese were never assimilated into the town’s population. Racial tensions resulted in Chinatown being burned at least four times. In 1879, following the last fire, tensions were near the breaking point and the Chinese began to arm themselves when they were prevented from rebuilding their homes. They were eventually “persuaded” to rebuild some of their homes south of the river. Tensions eased for a while, until the 1880s, when the American Workingmen’s movement coalesced under the slogan, “The Chinese must go.” The industrious Chinese, who had played such a key role in railroad construction, threatened to monopolize the local logging industry. In early 1886, the white citizens of Truckee banded together to rid the town of its Chinese population by forming a general boycott, refusing to buy from or sell goods to Chinese residents. Within nine weeks, the Chinese had been completely driven out of the community so thoroughly that for generations no Chinese could be found in or near Truckee. Logging was a key industry in Truckee over the past century. In 1866, Joseph Gray and George Schaffer built and operated the first lumber mill, which was located on the opposite side of the river from town. Schaffer later purchased Gray’s interest and in 1871, built a larger mill in Martis Valley, three miles south of Truckee. He also constructed a huge millpond in Martis Valley that now forms part of the lake next to the golf course in the Lahontan residential development.

|

Schaffer’s mill supplied lumber to the mines of Virginia City as well as to the growing cities of Sacramento and San Francisco. Schaffer later moved his mill a third time to a location further south where he built a home for himself and his workers near the bottom of today’s Northstar at Tahoe ski area.

Life in early Truckee was never dull. Money was plentiful, saloons and gambling houses attracted desperados of all kinds. Gunfights in the streets occurred almost nightly, many of which were consequential to disputes that occurred along Jibboom Street’s red light district. Numerous accounts of violence were published in the Truckee Republican, many chronicling tales of Jibboom Street’s infamous ladies of the night whose names included “Carrie (Spring Chicken) Smith;” “La Belle Butler” and “Lotta Morton.” In his book, “California Called Them,” historian Robert O’Brien writes,” Truckee went its own independent way and promptly became a juvenile delinquent among the California mountain towns.” “It was neither as raucous or as tough as Bodie,” writes O’Brien, “but it was trying hard for the same effect. The lights along Jibboom Street, a few steps from the main drag, were just as red as any that beckoned the swaggering, free-spending Bodie badmen. The nudes of the back bars of the front street saloons were just as lush as those you found in the plush-and-crystal bars along Virginia City’s C Street. In their book, “Sierra Nevada Lakes,” George and Bliss Hinkle, provide additional further insight into early life in Truckee: “The town had begun to acquire its peculiar character, compounded of an intense respectability, a taste for the more expensive refinements of life, such as good cigars, good champagne, and good oysters, a sportive flair, expressed in heroic poker parties, and an easy tolerance of one of the most raffish underworlds of the West.” One of the best portraits of life in early Truckee was published in a book by Isabella L. Bird entitled “A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains.” In the book, Bird tells of her 1873 train excursion to Lake Tahoe during which she spent a night in Truckee: “Truckee, the center of the lumbering region of the Sierras, is usually spoken of as a rough and tumble mountain town.” Undeterred by warnings of nightly “pistol affrays in bar-rooms” and that no “lady of respect” would ever be seen on the streets, Bird described what she saw upon stepping off the train: “The street, if street could be called which was only a wide, cleared space, is intersected by rails, with here and there a stump, and great piles of sawn logs bulking big in the moonlight, and a number of irregular clap-board, steep-roofed houses, many of them with open fronts, glaring with light and crowded with men, drinking and smoking. On the tracks, engines, tolling heavy bells, were mightily moving; the glare from their cyclopean eyes dulling the light of a forest which was burning fitfully on a mountain side; and on open spaces, great fires of pine logs were burning cheerily, with groups of men around them. A band was playing noisily, and the unholy sound of tom-toms was not far off.” After much difficulty, Miss Bird described checking into a hotel room at 11:30 P.M. and is told that no meal could be obtained at that hour. She describes being told that accommodations are too limited for the population of 2000, mainly masculine, and beds are occupied continuously, though by different occupants. “Consequently, I found the bed and room allotted to me quite tumbled looking. Men’s coats and sticks were hanging up, miry boots were littered about, and a rifle was in one corner. There was no window to the outer air, but I slept soundly, being only once awoke by an increase of the same din in which I had fallen asleep, varied by three pistol shots fired in rapid succession.” Upon awaking the following morning, Bird observed, “This morning, Truckee wore a totally different aspect. The crowds of the night before had disappeared. There were heaps of ashes where the fires had been. Only a few sleepy-looking loafers hung about in what is called the street. I stealthily crossed the plaza to the livery stable, the largest building in Truckee. Once on horseback my embarrassment disappeared, and I rode through Truckee, whose irregular, steep-roofed houses and shanties, set down in a clearing and surrounded closely by mountains and forest, looked like a temporary encampment.” Life in Truckee was constantly affected by frequent fires, including major conflagrations which occurred in 1868, 1869, 1871, 1873, 1875, 1878 and 1891. Undaunted by town fires, determined townspeople rebuilt, each time constructing better structures than before. As years passed, the early days of opium dens, gunplay, tar and featherings, and vigilantes gave way to more civilizing influences. The growing success of the lumber mills brought forth new entrepreneurial challenges, while the solid citizens of Truckee went about building schools and churches. In 1897, the Trout Creek Ice Company was formed followed by other ice companies which competed in producing ice for rail shipments to the east. Railroad operations also continued to figure prominently in the town’s activities, but the development of the automobile threatened its economic value. By the turn of the century, Truckee began promoting itself as the focus of a growing winter recreation region. Hollywood film companies, attracted by the area’s mountain charm, came to town establishing the town as a center for the budding motion picture industry. These changes were reflected in an article published in the Sierra Sun on January 12, 1972, by John Moretta, who recalled the pre-World War I days in Truckee: “Behind the main street was a street for houses of easy virtue and two dance halls, the ‘California,’ and the ‘Monte Carlo.’ The bars were the men’s own domain; even women entertainers were barred. The bars catered to the many single males who worked in the lumber industry and ice camps.” “Men were pretty rough in those days, but it was a nice area to live in. It was a big family,” he recalled, with a population of perhaps 800, all clustered together in the center of town. It was a life in which people lived simply, they helped one another. The doors of homes often were lockless. “If somebody had a little hard luck, everybody would want to do something for them. People looked out for one another.” Moretta recalled that on Sundays, everyone dressed up and went to church, including the old drunks, who afterwards would then return to the saloons and get drunk again. “It was a happy go lucky time. People worked harder, but also rested better at night. The people then weren't so much out for money as they are today. They were happy to be living, to be able to eat.” In a book published in 1983, the late Tony Pace reflected on his observations of how life in Truckee has changed. “I think the reason that Truckee is changing so much is that all the people in California are looking for a place to get away from the city, so they move to Truckee.” Pace added, “It’s just turning into a city, and there is nothing to stop it.”

As demand for lumber decreased, many mills were forced to close, including Schaffer’s operation in Martis Valley. However, there were two other industries that were quite large at one time. Before the invention of artificial refrigeration, large amounts of ice were needed in cities from San Francisco and Los Angeles, as far away as New Orleans. Tons of ice blocks were cut from ice ponds on Donner Lake and Boca. These ice blocks were then packed in sawdust or hay to keep them from melting and shipped by rail. Boca also had a lumber mill operation in 1866, but became known worldwide in 1883 when a brewery was constructed next to the Truckee River. The clear, pure water of Boca that created such a demand for ice also lent itself to brewing beer with mountain water long before Coors was fashionable. Many thousands of barrels of ice cold Boca Beer were shipped throughout the United States and the product gained worldwide recognition. By 1915, Truckee became a favorite area for winter sports, featuring a huge ice palace for ice-skating and dancing, a toboggan slide and ski jump. The Truckee Ski Club was formed and its members participated in many competitions. Special excursion trains brought thousands of visitors to the area to enjoy the fresh air and to frolic in the snow. The movie industry brought crews to the area to film winter scenes. Famous movie actors became a familiar site on the streets of Truckee. After the 1920s, Truckee began a 40-year period of little growth and development, particularly during and after World War ll. Finally, in 1960, the Winter Olympic games were held ten miles to the south at Squaw Valley, putting the Truckee-Tahoe area on the map as a major destination resort for year-round recreation. Today, tourism has become the area’s lead industry, but as the town continues to grow, it is also diversifying. |