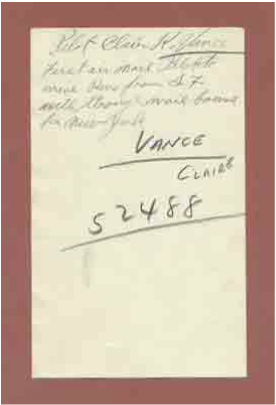

In the 1920s a new breed of pioneers came to the Sierra. Airplanes first crossed the Sierra in 1919, and in 1920, the U.S. Government started the U.S. Air Mail Service. They chose young but experienced aviators, mostly World War One Veterans to fly the dangerous routes across the country. One of the most daring, most famous and well liked was Claire Vance.

Vance started out as a World War One pilot, serving as the youngest commissioned aviation officer in France, and earning the Ace designation. He taught new pilots and became a top instructor very quickly. He never was shot down, but crash landed a few times. He was known to be a natural flier and master of his ship in emergencies.

After the war Vance taught flying to new private pilots, but when the new Air Mail Service was established in 1920 he signed up. He thrilled at flying and especially over the Sierra, which was a breeze on a sunny summer day.

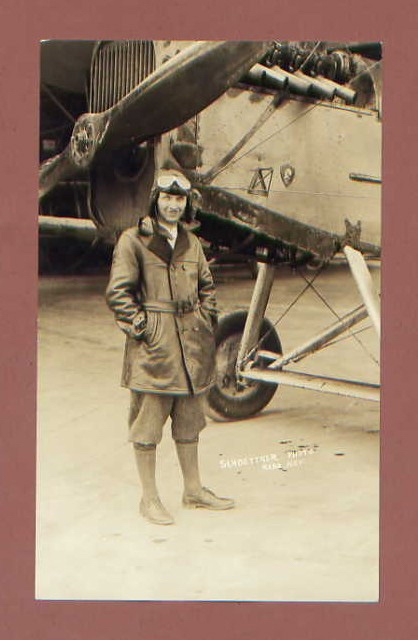

With the traditional leather cap and goggles, Vance braved all but the fiercest storms that the Sierra threw at him. Often enough winter storms prevented most pilots, even Vance, to wait out the storm in Reno or Sacramento. All this in a wood framed, cloth covered, open cockpit biplane.

He had many adventurous moments over the Sierra in his career on the San Francisco-Reno-Salt Lake City route. From 1922 on he flew 3500 trips logging 8000 hours, 2000 hours of that night flying

The Ups and Downs of Flying

On one memorable trip crossing the Sierra, his airship dropped several thousand feet over Donner Lake in a downdraft, gaining control only a few hundred feet over the frozen lake. In the winter of 1923 his engine went out over Donner Pass and he brought his aircraft to a safe forced landing on the Summit.

On another crossing in a blizzard, when other pilots were grounded, Vance hit a wall of fog, snow and ice high over the summit that filled up his open cockpit. He tried to keep his instruments and gauges clear of ice and his goggles from fogging up. He was absolutely lost and confused in hurricane force winds.

He went into a tailspin when his control stick was clogged with snow and ice. After dropping 8000 feet he regained control and flew out of danger. He commented that it was the "nearest shave to a washout I’ve ever had-that’s all."

In 1923, while over San Francisco Bay, he was testing out a new mail plane when the engine went out and he was forced down into the water. After a long hour floating along, a tugboat rescued him.

A few weeks later he had to fly straight up to 12,000 feet to avoid fog and clouds over San Francisco. He flew over the clouds all the over the Sierra, spying a small hole over Donner Lake, then zooming to within 50 feet of the ground as he flew down the tortuous and foggy Truckee River Canyon. He flew into Reno, brushing building tops in the dark. He landed in the unlighted, unmanned field, pulled up to the hanger and startled the night watchman.

On the next weeks trip, he got lost in the fog near Blue Canyon at 15,000 feet, when suddenly he plummeted 4000 feet and found himself flying upside down and in a deadly tailspin. He dropped to within 200 feet of the ground before he gained control and leveled off. After clearing his goggles, he flew on to Reno and delivered the mail on time.

Vance started out as a World War One pilot, serving as the youngest commissioned aviation officer in France, and earning the Ace designation. He taught new pilots and became a top instructor very quickly. He never was shot down, but crash landed a few times. He was known to be a natural flier and master of his ship in emergencies.

After the war Vance taught flying to new private pilots, but when the new Air Mail Service was established in 1920 he signed up. He thrilled at flying and especially over the Sierra, which was a breeze on a sunny summer day.

With the traditional leather cap and goggles, Vance braved all but the fiercest storms that the Sierra threw at him. Often enough winter storms prevented most pilots, even Vance, to wait out the storm in Reno or Sacramento. All this in a wood framed, cloth covered, open cockpit biplane.

He had many adventurous moments over the Sierra in his career on the San Francisco-Reno-Salt Lake City route. From 1922 on he flew 3500 trips logging 8000 hours, 2000 hours of that night flying

The Ups and Downs of Flying

On one memorable trip crossing the Sierra, his airship dropped several thousand feet over Donner Lake in a downdraft, gaining control only a few hundred feet over the frozen lake. In the winter of 1923 his engine went out over Donner Pass and he brought his aircraft to a safe forced landing on the Summit.

On another crossing in a blizzard, when other pilots were grounded, Vance hit a wall of fog, snow and ice high over the summit that filled up his open cockpit. He tried to keep his instruments and gauges clear of ice and his goggles from fogging up. He was absolutely lost and confused in hurricane force winds.

He went into a tailspin when his control stick was clogged with snow and ice. After dropping 8000 feet he regained control and flew out of danger. He commented that it was the "nearest shave to a washout I’ve ever had-that’s all."

In 1923, while over San Francisco Bay, he was testing out a new mail plane when the engine went out and he was forced down into the water. After a long hour floating along, a tugboat rescued him.

A few weeks later he had to fly straight up to 12,000 feet to avoid fog and clouds over San Francisco. He flew over the clouds all the over the Sierra, spying a small hole over Donner Lake, then zooming to within 50 feet of the ground as he flew down the tortuous and foggy Truckee River Canyon. He flew into Reno, brushing building tops in the dark. He landed in the unlighted, unmanned field, pulled up to the hanger and startled the night watchman.

On the next weeks trip, he got lost in the fog near Blue Canyon at 15,000 feet, when suddenly he plummeted 4000 feet and found himself flying upside down and in a deadly tailspin. He dropped to within 200 feet of the ground before he gained control and leveled off. After clearing his goggles, he flew on to Reno and delivered the mail on time.

The Leading Pilot

Vance set speed records in 1921 on the Reno-Elko leg flying at 176 miles an hour in a open pit biplane. This was on a routine flight, all in a days work for the air mail pilot. Vance had another hair raising event that will be told in another article.

When brother air mail pilot William Blanchfield was killed near the Reno flying field, Vance was the one who suggested the airfield be renamed Blanchfield for his friend, and so it was before it became Reno Airport. Vance performed a tribute flight over Blanchfield’s funeral, hoping he wouldn't suffer the same fate.

When 24 hour mail service was inaugurated in July of 1924, Vance brought the first mail pouch over the Sierra. Vance was one of the pioneers of Sierra night flying, relying on moonlight to navigate his way from San Francisco to Reno. He battled a thick bay Area fogbank for an hour before breaking into sunshine, then sped over the Sierra arriving ahead of schedule.

As new planes were developed for the Air Mail service, Vance was the leading test pilot in the West. Up until 1926 the pilots were still flying wooden World War One design De Haviland biplanes, but the new Douglas wing steel construction biplane with an enclosed cockpit soon became the standard plane.

The Boeing Connection

The Western U.S. Air Mail contract was given to Boeing in 1927 and the pioneer period of aviation history came to a close. Soon after that Boeing put the tri-motor airship into service and the safety, comfort and reliability of the trans-Sierra trip increased. The goal of the contract was to encourage commercial passenger service and soon after that planes were full of long distance travelers.

Vance, one of the first Boeing pilots, still felt the thrill of the flight as weather would constantly change, and there was always something new to see, even at 12,000 feet of altitude. When the first scheduled transcontinental airline service in 1931, Vance was one of the selected pilots. When United Airlines took over all flight service from Boeing, Vance was one the first pilots hired.

In 1922 the Vance Aircraft Corporation was formed to build the new Vance designed plane. It was one of the first high speed long distance single wing planes, dubbed “The Flying Wing” which led the way for modern aircraft. This 700 horsepower twin tail sleek speeder was designed for long distance flight as well as stability in intense windstorms. Vance made many cross country flights pushing the limits of aviation.

Claire Vance had dozens of close calls over his career, always knowing that death was just a moment away. Mostly he flew by the seat of his pants, keeping close enough to the ground where he could to keep his bearings. As the 1930s dawned, instrument flight began to be incorporated in commercial aviation, and Vance began to rely less on his instincts and more on technology.

The Last Run

On December 17, 1932, Vance was flying his normal route from Oakland to Reno. Relying on the new instruments rather than his brains, he flew off and radio contact was lost. For two days every available plane in the Bay Area flew search missions looking him. His brother, air mail and Boeing pilots searched frantically, but knowing Vance they felt that he would turn up safe and sound.

Unfortunately Vance’s plane was found at the top of Rocky Ridge near Danville. He crashed in the fog, missing the top of the ridge by ten feet. The impact caused his immediate death and airship burst into flames and burned. Vance died doing what he loved, his thrill in life being the freedom of flight.

Even after his death, Vance was remembered, as a hero of a dozen exploits. He was additionally remembered as his “Flying Wing” design became incorporated in many of the new commercial and military planes being built in the pre World War Two years.

Vance set speed records in 1921 on the Reno-Elko leg flying at 176 miles an hour in a open pit biplane. This was on a routine flight, all in a days work for the air mail pilot. Vance had another hair raising event that will be told in another article.

When brother air mail pilot William Blanchfield was killed near the Reno flying field, Vance was the one who suggested the airfield be renamed Blanchfield for his friend, and so it was before it became Reno Airport. Vance performed a tribute flight over Blanchfield’s funeral, hoping he wouldn't suffer the same fate.

When 24 hour mail service was inaugurated in July of 1924, Vance brought the first mail pouch over the Sierra. Vance was one of the pioneers of Sierra night flying, relying on moonlight to navigate his way from San Francisco to Reno. He battled a thick bay Area fogbank for an hour before breaking into sunshine, then sped over the Sierra arriving ahead of schedule.

As new planes were developed for the Air Mail service, Vance was the leading test pilot in the West. Up until 1926 the pilots were still flying wooden World War One design De Haviland biplanes, but the new Douglas wing steel construction biplane with an enclosed cockpit soon became the standard plane.

The Boeing Connection

The Western U.S. Air Mail contract was given to Boeing in 1927 and the pioneer period of aviation history came to a close. Soon after that Boeing put the tri-motor airship into service and the safety, comfort and reliability of the trans-Sierra trip increased. The goal of the contract was to encourage commercial passenger service and soon after that planes were full of long distance travelers.

Vance, one of the first Boeing pilots, still felt the thrill of the flight as weather would constantly change, and there was always something new to see, even at 12,000 feet of altitude. When the first scheduled transcontinental airline service in 1931, Vance was one of the selected pilots. When United Airlines took over all flight service from Boeing, Vance was one the first pilots hired.

In 1922 the Vance Aircraft Corporation was formed to build the new Vance designed plane. It was one of the first high speed long distance single wing planes, dubbed “The Flying Wing” which led the way for modern aircraft. This 700 horsepower twin tail sleek speeder was designed for long distance flight as well as stability in intense windstorms. Vance made many cross country flights pushing the limits of aviation.

Claire Vance had dozens of close calls over his career, always knowing that death was just a moment away. Mostly he flew by the seat of his pants, keeping close enough to the ground where he could to keep his bearings. As the 1930s dawned, instrument flight began to be incorporated in commercial aviation, and Vance began to rely less on his instincts and more on technology.

The Last Run

On December 17, 1932, Vance was flying his normal route from Oakland to Reno. Relying on the new instruments rather than his brains, he flew off and radio contact was lost. For two days every available plane in the Bay Area flew search missions looking him. His brother, air mail and Boeing pilots searched frantically, but knowing Vance they felt that he would turn up safe and sound.

Unfortunately Vance’s plane was found at the top of Rocky Ridge near Danville. He crashed in the fog, missing the top of the ridge by ten feet. The impact caused his immediate death and airship burst into flames and burned. Vance died doing what he loved, his thrill in life being the freedom of flight.

Even after his death, Vance was remembered, as a hero of a dozen exploits. He was additionally remembered as his “Flying Wing” design became incorporated in many of the new commercial and military planes being built in the pre World War Two years.